Miniature Form in Electroacoustic and (Instrumental) New Music

A typology supported by an audio gallery in order to establish a conclusive definition of “miniature form”

In recent decades, in both the instrumental New Music and electroacoustic milieux, there has been a slowly growing interest in works having a duration of less than a specific threshold. Accompanying this trend there has been, however, a surprising shortfall of reflection and discussion on the actual criteria and characteristics of the “miniature” or the “short work”. With a number of projects promoting the form now having been realized and a large number of works available which are considered to be miniatures, it is now possible to assess more the nature of this particular musical form by asking such questions as: Why it is relevant or interesting to compose in this form(at)? More fundamentally, what in fact constitutes a “miniature”? The many discussions that have attempted to address the differences between miniature and non-miniature form have typically concerned duration almost exclusively, with no conclusive justification of why one particular duration — varyingly 60 or 90 seconds, 3 minutes or 5 minutes — can convincingly be deemed to be the appropriate threshold defining a work as a miniature.

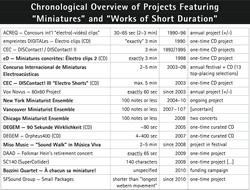

An overview of a quarter century’s worth of competitions, CD projects, instrumental ensemble programmes and more, in which “miniatures”, “electro-clips” and “works of short duration” were featured, will show just how varied and conflicting the ideas about “miniature form” can be — for composers, producers and institutions alike. Key elements of each of these projects are articulated with the goal of making a general comparison of the intentions of these projects and clarifying what aspects of miniature form were presumed, known, reflected upon, proposed, ignored or advanced by the individuals and institutions involved. In parallel to sorting through these projects and the works that were part of them, a plethora of individual pieces from a large number of sources were also consulted.

This larger library of works and projects was used to extract and develop a comprehensive yet flexible definition of miniature form, as well as a set of distinct categories and subcategories for the miniature. Finally, each of these categories is illustrated by compositions that effectively reflect their specific nature; each work’s correspondence to a specific form is explained in a succinct manner and the reader is invited to compare and confirm — or refute! — the correspondence by listening to the audio examples available for each piece.

The concept of “miniature form” has had a varied recent history but is still lacking in a clear identity. This article intends to provide the first comprehensive proposal for a definition of the miniature and a typology of miniature forms.

Comparitive Overview of Projects Featuring “Miniatures” and “Works of Short Duration”

The following overview of projects that — explicitly or not — were concerned with “miniature form” or “works of short duration” is by no means exhaustive. It should be sufficient, however, to provide some perspective on the range of approaches to and understanding of such forms in the past quarter century 1 (#1)[1. The discussion of Chopin’s Études or much of Webern’s catalogue as being precursors to miniature form (as we understand the term today) is entirely relevant but will not be addressed here. Here the focus is on the definition and the categorization of miniature form in relation to works in recent musical history. The larger historical development of the miniature should, however, be addressed in a separate, dedicated article.], and to articulate some of the tendencies that have emerged. Grouped in categories according to their nature, a brief history, background or the raison d’être for each of the projects is given, complemented by any information concerning the definition of “miniature form” implied or stated by the organizers.

Competitions and Festivals

Concours international « électro-vidéo clips » (Canada: ACREQ, 1990–96)

In the early 1990s, the Montréal-based Association pour la création et la recherche électroacoustiques du Québec (ACREQ) expanded its activities to promote and produce projects not just by electroacoustic composers, but also by “sound and video artists”, offering them an “original artistic challenge, combining a spirit of imagination, audacity, humour and provocation” (Westerkamp 1993, 4).

The idea of the project had its genesis following a concert presented by ACREQ. Yves Daoust, then president of ACREQ, had commented on the disproportionate length of some of the electroacoustic pieces in the concert and “mentioned that it would be interesting to mount a concert consisting only of short pieces.” Picking up on the idea, ACREQ member Myke Roy, with the help of pianist Jacques Drouin, developed the idea and “rules” for what would become the Électro Clip competition, launched in 1990 with an international call for electroacoustic works with a minimum duration of 0:30 and maximum of 1:05. On this particular choice of duration, Roy said: “It was an arbitrary choice. It seemed to me that doing a piece between 0:30 and 1:00 was a greater challenge than 2 to 3 minutes” (Roy 2010). The project also made it possible to programme a larger number of composers, including in particular those whose works might actually fare better in a smaller form (Bouhalassa 2010). For some, the smaller form of the “electro clip” offered respite from the onslaught of excessively long electroacoustic works that were somewhat common at the time, and concerns about alienating the audience could be alleviated through the promotion of a smaller form that possibly made it “easier to ‘digest’ ea” (Ibid.).

According to the call for submissions for the third edition in 1993, ten audio and ten video miniatures of two to three minutes duration were to be selected as finalists and performed at a Gala event on 30 May, three winners would receive prizes of audio-visual equipment and the audio finalists would be published on a CD (Westerkamp 1993, 4).

The organizers had no intention for the project to have a long-term effect, to “start a fad of [composing] miniatures”; it was in fact initially intended as a one-off event offering a challenge to composers (Roy 2010). The project, however, lasted for six editions (1990, 1992–96). By the third edition 2 (#2)[2. It has not been possible to establish whether or not the change had been made already as of the second edition.], the submission criteria had expanded to allow for the inclusion of video or audio-video works, and the project was renamed the International Électro-vidéo Clips Competition.

Concurso Internacional de Miniaturas Electroacústicas (Spain, 2003–09)

First produced in 2003, the Concurso Internacional de Miniaturas Electroacústicas held annually in Huelva, Spain, was perhaps the best known project having the specific aim to promote compositions in miniature form in recent years. For each edition, a total of 13 internationally based finalists were retained — ostensibly because that was the number works under five minutes in duration (i.e. 65 minutes) that would fit on the CD published as part of the prize packages. The project was quite popular and quickly gained renown, but its growth was abruptly stopped in 2010 when arts council funding was ceased (Polonio 2010).

The organizers of this project aimed to distinguish it from other similar calls for works by insisting that the works submitted must be “sonic miniatures using the language of electroacoustic music” and be between a minimum of two and maximum of five minutes in duration (Confluencias 2003). Given the fact that works that did not respect these limits risked being disqualified (Ibid.), many pieces unsurprisingly fall within half a minute of the criteria. But there are several cases where the works submitted were in fact excerpts of significantly longer works.

In the 2008 edition of the Concurso, five of the selected works (38%) had a duration that was within five seconds of the 5:00 limit; in 2007, five were within 15 seconds of the limit. This of course begs the question of whether the pieces had been tailored, edited down, to fit the eligibility criteria, and were not in fact, as required by the official rules of the competition, “sound miniatures” of a minimum of two and maximum of five minutes in duration. And in fact, it is not difficult to find works amongst the finalists in this competition that had been edited down to fit the eligibility criteria — there were five in the 2007 edition. The overall spread of durations is a little more “natural” — from a compositional standpoint — in this competition than in some of the CD compilations discussed below, but this is quite likely due in part to the longer duration limit in the Concurso.

Música Viva Festival — “Sound Walk” Project (Portugal: Miso Music, since 2008)

Starting in 2008, in parallel to their general call for submissions for the annual Música Viva Festival, Lisbon-based Miso Music put out a call for miniatures for a soundwalk installed for the duration of the festival. Each year, 25–35 pieces were selected from 100–150 submissions for inclusion in the project. There was no statement offered by the organizers concerning their views on or interest in the nature of miniature form; the rules for submission seem to provide the only indication of their position on the matter. And in fact, the first three of these rules, indeed the most critical and defining ones concerning form and submission protocols (no age or nationality restrictions; sound miniatures in electroacoustic language of 2–5 min. duration; limit of one piece per composer), as well as the final rule (submission implies acceptance of the rules) were plagiarized virtually word for word from the Huelva competition (Confluencias.org 2005; Miso Music 2011).

Compilation CD Projects

Électro clips (Canada: empreintes DIGITALes, 1990)

This disc appears to be the first published compilation of electroacoustic works of short duration and features 25 “electroacoustic snapshots” commissioned explicitly for CD publication from composers living in North America. The liner notes do make mention of the word “miniature”, but descriptively, not prescriptively; the term “électro clip” was already starting to circulate in the electroacoustic milieu (Denis 2010), thanks to the ACREQ project mentioned above. The organizers of this project, Jean-François Denis and Claude Schryer, also the founders of the label on which it was published, were more explicitly concerned with the idea of “merging the pop form (of a three-minute duration) with the concept of the ‘video clip’” in order to transport the works out of the concert hall into the “mediatic world of the clip, of the instant, of the immediate” (Denis and Schryer 1990) than with the exploration or definition of miniature form as such. They emphasize that the disc is “more than a collection of short pieces,” that “each miniature” (italics mine) published on the CD also offers a sort of précis of the artist’s style.

The composers of all 25 works on the CD strictly followed what seem to have been fairly rigid rules of participation — the vast majority of them are within two seconds of the three-minute duration limit, with none diverging more than five seconds from it.

DISContact! I / DISContact! II (Canada: CEC, 1992 / 1995)

The first in the DISContact! series of double-CD compilations features 40 tracks composed by members of the Canadian Electroacoustic Community (CEC) living in Canada at the time. The tracks are for the large majority (almost 90%) excerpts from works-in-progress or completed works that are either truncated or faded out to the right duration. There are, however, some complete pieces on the disc, and a couple of these were composed explicitly for the publication. The CD was intended as a promotional tool for CEC members, and while the “electro clip” was certainly familiar to the production group coordinating the project, the 3:00 limit of duration seems to have functioned more as a practical consequence of participating in the project than an æsthetic challenge to the composers.

Of the 38 short works on the CD, 26 (68%) are within 15 seconds of the 3:00 limit and 29 (76%) are within 30 seconds. Only 7 pieces are around the 2:00 mark or less. Surprisingly, despite the large number of excerpts on the CD, some of these pieces, even those that fall particularly close to the limit (which we might imagine could have suffered more from forced editing), do seem to have a convincing “closed” form. Of course, someone might propose that a “clip” does not necessarily have to be a complete piece…

For the second publication in the DISContact! series, promotion of CEC members was still the primary interest, but by now the CEC’s membership had expanded significantly and it had members not only in Canada, but also in the USA, Japan and Europe. In addition to a far smaller percentage of pieces that are excerpts of larger works (11 of 51, or 22%), a much broader range of durations is found on this CD in comparison to the first in the series. Still, half the pieces are within 15 seconds of the 3:00 limit, three-quarters within 30 seconds and only four pieces are 2:00 or shorter, the shortest a mere 0:37.

Miniatures concrètes: Électro clips 2 (Canada: empreintes DIGITALes, 1998)

With this follow-up to their 1990 CD compilation, the label aimed to celebrate the 50th anniversary of musique concrète in as broad a manner as possible. To that end, they commissioned 24 works of exactly 3:00 duration from composers around the world and provided three short audio bites that were to be used as source material in the work; the composers were free to use their own materials as well. There is no other mention of the term “miniature” in the publication than in the actual CD title, Concrete Miniatures; in the brief liner notes the publisher speaks in passing of “short works” and the term “miniature” is not to be found in any of the programme notes.

DISContact! III (Canada: CEC, 2003)

In response to an international call for submissions, over 100 works were sent in to be considered for inclusion on this double-CD dedicated to the “electroacoustic piece of short duration, or electro-clip” (CEC 2003). A quarter of the submissions came from Canada, another quarter from the USA and the rest came from around the globe, reflecting the CEC’s commitment to promoting and fostering electroacoustic music and sonic art from Canada and abroad.

The organizers of the project stated at the time of its publication that “the electro-clip has become an integral part of the electroacoustic establishment” (Ibid.). Indeed! Amongst the submissions to this project we find not only a greater range of durations that are not “very close” to the time limit, but also — for the first time — several work titles implying the composer’s interest in or awareness of the implications of composing in a smaller form: At Last the Two-Minute Day! (de Moncey-Conegliano), Your 3-Minute Mardi Gras (DeLaurenti), A Short Tale (Fischman), 2 minuti di raccoglimento (Garau), Four More Sho(r)ts (Rebelo), Electroclips (Sundin).

Although for this third compilation CD in the series there is a more explicit use of a specific term to address the nature of the “work of short duration”, the organizers go no further than to point out that all works included on the disc are under five minutes in length. Confusing matters even more, the CD liner notes mention “both the electro-clip and its somewhat longer sibling, the electro-short” (PeP 2003), with no clarification of what the difference between the two is. Still no clear definition of the miniature in sight, but at least now we are making progress.

90 Sekunde Wirklichkeit (Germany: DEGEM, 2005)

Coordinated by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik (DEGEM), Germany’s national electroacoustic association, and curated by New Music promoter Stefan Fricke, the CD compilation 90 Sekunde Wirklichkeit [90 Seconds of Reality] features 47 works by composers from or living in Germany at the time of the production.

Miniature form is mentioned almost as an afterthought at the very end of the liner notes. The project is about “miniatures, shards of reality, each about 90 seconds in duration”, writes Fricke (2005), but his use of the term is more analytical — describing the results as miniatures after the fact — than a proposal about what that form actually is or can mean, how we might understand it in the context of these moments of reality. Three composers (of 47) explicitly use the word “miniature” in their programme notes (available on the DEGEM website), but again only as a descriptor.

All works on this CD were composed specifically for the project, so the durations on the CD are ostensibly the real durations of the works (i.e. there are no excerpts). And they are in strict accordance with the concept and title of the CD — none is more than a second longer than 90 seconds, not a single work is shorter. However, several endings of the pieces have brutal edits; we might be inclined to assume this indicates that the piece submitted by the composer was in fact longer in its original form, but was edited down (by the composer or the producer) to “fit” the project.

Orpheus 400 (Germany: DEGEM, 2007)

The concept behind this CD published by DEGEM was a commemoration of, firstly, the 400th anniversary of the production of Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, “the first high point of musical theatre” (Fricke 2007) and, secondly, the “scandalous” Donaueschingen premiere of Orphée 53, the first “concrete opera”, composed in 1953 by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry for three voices, harpsichord, violin and tape.

With a single exception, all works on this CD compilation (also curated by Stefan Fricke) were composed for the publication. Miniature form in this context is little more than a result of the conceptual structure of the project, which presents 20 electroacoustic pieces offering “extremely diverse readings of the myth: orphic abridgements of between four and 400 seconds in duration” (Fricke 2007).

Ensembles

New York Miniaturist Ensemble (USA, 2004–10)

Formed by Juilliard graduates in 2004, The New York Miniaturist Ensemble (NYME) promoted and performed works composed of “100 notes or fewer” (Bruce 2006; NYME 2010), although there was no criteria that specifically stipulated that composers must limit their compositions to this number. The ensemble’s definition of a miniature raises a question that is perhaps impossible to answer definitively, miniature or not: “Just what, exactly, is a note?” (CME 2008)

Over 200 composers wrote works for the ensemble, including several well known and internationally recognized composers, from Finnissy to Bussotti to Pousseur and beyond (NYME 2010). Judging by photos and information posted to the NYME Facebook page’s “Events” tab 3 (#3)[3. This information was available in January 2013 but but neither the website nor the Facebook page for the ensemble exist anymore.], it seems their last concerts were on 26 September 2009 (included a premiere of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s First Natural Durations [2005/3:00], commissioned by the ensemble), 30 October 2009 (included a premiere of Alvin Lucier’s Miniature for Clarinet and Cello) and 25 February 2010 (a programme of violin duos). The programme of the latter concert was unique for NYME in that, in addition to new works by living composers, it included repertoire by such composers as Bach, Berio, Bartók and Schoenberg.

It seems that NYME was open to receiving unsolicited works written for the ensemble, but it was suggested that these works should correspond to one of three types of instrumentation: solos, duos or trios with combinations of violin, clarinet (B-flat or bass) and piano; soprano and piano duo; violin duo (NYME website 2013). We can therefore infer that the full ensemble was made up of voice, clarinet, two violins and piano. As quartet and quintet formations were seemingly not admissible to the project, we could assume that the instrumentation was meant to mirror the reductive approach to composition that the ensemble dedicated itself to promoting.

Vancouver Miniaturist Ensemble (Canada, 2007[–10?])

In 2007, the Vancouver Miniaturist Ensemble was founded “a group of Vancouver musicians inspired by the work of the New York Miniaturist Ensemble” (VME 2010). Their mandate was to perform, like the NYME before them, works of 100 notes or less. However, VME expanded on NME’s idea and aimed to build a repertoire made up of “newly composed works expressly intended to explore the miniature genre as well as previously existing works.” The ensemble’s MySpace page offered information suggesting they would have considered performing works of a more distant past than those they performed by Stockhausen (Tierkreis, from 1974–75) and Feldman (Only, from 1947), provided the works fit the ensemble’s 100-note criteria 4 (#4)[4. “Our mandate is to perform works, whether ancient or modern, that consist of one hundred notes or less.” (VME 2010)]… which they, like the NYME before them, did not explain.

Chicago Miniaturist Ensemble (USA, 2008)

A “motto” found on the Chicago Miniaturist Ensemble (CME) website stands as a humorous miniature manifesto: “Life is complicated. Get to the point” (CME 2008). Using the same model as the New York ensemble, CME was also dedicated to the performance of existing and new pieces that were composed of “100 notes or fewer.” Two calls for new works were sent out by the ensemble, which performed two concerts in total, on 27 September 2008 and 8 December 2008.

Although CME didn’t provide any more precision than NYME in regards to the answer to the question “What is a Note?”, several more questions were proposed as points for reflection in a tab on their website devoted to the initial question (Ibid.):

- Are pitch inflections (i.e., grace notes, pitches included in trills or glissandi) notes?

- Are non-pitched rhythmic events notes?

- Are the syllables of spoken words or narration notes?

- Do consecutive rearticulations of a single pitch count as separate notes?

- Do octave doublings count as separate notes?

The question is now more open than ever, but the ensemble felt that the 100-note issue was “a question that each composer can answer individually” (CME 2008). One could assume that by steadfastly refusing to give the composers any clear or specific directives, the ensemble was hoping to receive a collection of very diverse — and perhaps sometimes contradictory — answers to the questions raised around the idea of the 100-note form.

Bozzini Quartet — Call for Commissions: À chacun sa miniature! (Canada, 2010)

Montréal-based string quartet Quatuor Bozzini launched a funding project in 2010 in order to raise $20,000 CAD in donations from Québec residents, which was matched at a proportion of 3:1 by a programme called Placements Culture, coordinated by the Conseil des arts et lettres du Québec (CALQ), allowing the ensemble to establish a permanent endowment of $80,000.

The donations — which became part of the endowment fund — were used to “sponsor” portions of new compositions written for the quartet by young composers who were alumni of the group’s Composer’s Kitchen project between 2005–10. Via an interface on the donations page it was possible for financial donors to add values in $50 increments (one second cost $5.00) and thereby personalize contributions according to their budget and/or desired “gift” for their donation, which were as follows (Quatuor Bozzini 2010):

- Less than $100: Simple Donation

- $100 and over: Dedicate the music to a loved one.

- $200 and over: Describe the personality of your dedicatee.

- $300 and over: Give a direction to the composer for the general characteristics of the music.

- $400 and over: Receive, as well as your dedicatee, the signed musical score with your dedication.

- $600 and over: Choose the composer from our list of candidates.

- $800 and over: Your complete miniature commission (160 sec.) allows you to attend a rehearsal.

- $1000 and over: We will give you a ringtone for your cellphone with music from the miniature you have commissioned.

No explanation or definition of what a “miniature” was could be found on the website or in announcements about the project. 5 (#5)[5. Requests via email to answer this question were also not answered.] The only mention of duration in relation to a composition appeared in the explanation of the “$800 donation” benefits (above). In fact, the interface allowed the user to contribute more than $15,000 6 (#6)[6. Donating more seemed to be possible, but I stopped clicking at $15,050, the point having been made.] in order to “commission” a 50-minute work — hardly a miniature by anyone’s account! The project was obviously built around a question of expediency to gather donations in an efficient and flexible manner; the language of the used in the project was built around monetary values, not musical form or compositional intent.

Despite the apparent openness of the call in terms of duration, it seems there was no correlation between the donation of a single user and the work that the donation sponsored in part. On the double-CD documenting the project, durations range from 1:39 to 4:51, falling completely in line with the “norms” of duration for miniatures. 7 (#7)[7. Presumably it was the composers themselves who decided on the length of the individual pieces, possibly for compositional reasons, but this does not seem to be documented.] Of 30 works, 18 are within 30 seconds of a 3:00 ($900) duration, only five are under 2:00 ($600) in length, only two are over 4:00 ($1200) and none are under 1:30 ($450) or over 5:00 ($1500).

SFSound Group — Small Packages (USA, since 2010)

Small Packages is a concert project coordinated by the San Francisco / Bay area ensemble SFSound Group first presented in 2010 and still running as of December 2014. For the first edition of the project, 15 local composers were invited to compose short works for the group that were “no longer than the longest webern movement”; this number of pieces was chosen because “it seemed the right amount to make a full program” (Ingalls 2010). The format was changed slightly for the second edition in January 2010 in order to build a concert programme that presented a slightly smaller selection of new “small packages”, having a maximum duration of 5:00, alongside one important New Music work; this is also the format of the latest edition by the group, presented in August 2014.

There is no specific mention of miniature form, or even of form, anywhere in the project. The aim of the project is rather to create programmes that present a larger number of new works by younger local composers than would be possible in the standard concert format, featuring longer compositions.

Other

A-Line (Berlin: Folkmar Hein, 2001)

In this project organized by Folkmar Hein, Director of the electroacoustic studios at the Technische Universität Berlin (Audio Communications), 20 pieces of exactly one minute each were presented in an installation that ran during the 2001 edition of Berlin’s annual Lange Nacht der Museen (Long Night of Museums). Hein is known for his enthusiastic advocacy of multi-channel works, and so for this project, all works were composed explicitly for the 16-speaker system installed in a straight line in the foyer of the math pavilion of the TU. 8 (#8)[8. This project was brought to my attention only recently by Hein during a presentation I gave near the completion of this article. I would expand on the the minimal amount of information included here in a future article if possible.]

60x60 Project (New York City: Vox Novus, since 2003)

Vox Novus produced the first 60x60 event in New York City in late 2003 and the project has since been presented hundreds of times around the world: already in 2004 there were 15 presentations of different regional “mixes” throughout the US, as well as in Romania and Turkey. In recent years there have also been themed calls for works, for example a Latin Mix and a “BPM (beat party mix)” in 2014. The project extends an international call for “signature works” having a duration of exactly 60 seconds that are created specifically for the project. A selection of the submissions is made in order to build a 60-minute concert programme of 60 such works played back to back without pause. No suggestions are made by the organizers in terms of form, style or genre, as the goal is to present as broad a range of pieces as could be possible. The diversity built into the programming is borne out of a commitment of the project’s founder and director, Rob Voisey, to “disseminate a cross-section of æsthetics in an exciting format to a broad spectrum of people” (Voisey 2009).

Folkmar Hein’s 65th Birthday and Retirement Concert (Berlin: DAAD, 2009)

In spring 2009, following 35 years as Director of the electroacoustic studios at the Technische Universität Berlin (Audio Communications), Folkmar Hein celebrated his 65th birthday and retired from his post. Ingrid Beirer (DAAD Music Director), along with Volker Straebel (new Co-Director of the studios) and Carsten Seiffarth (Artistic Director of Singuhr-Hörgalerie), began in late 2008 to coordinate a tribute concert for Hein to mark the occasion. Composers and sound artists who had worked in or who were otherwise connected to the studios since 1974 were invited to compose a new stereo or 5.1 work for the concert; the organizers received 77 contributions for the event. The compositions, as would be expected for such an eclectic range of composers as the studios had supported over the years, were extremely varied in style, character, concept and intimacy, and in the end the concert programme was a colourful collection of brand new electroacoustic works, live performances, alternate versions of existing pieces, sonic poems and sonified anecdotes, playful explorations of Folkmar’s pet peeves and sonic fetishes, and more.

The prescribed duration in seconds of the pieces was the very concrete number of years since Folkmar was born. Despite there being no mention (for obvious reasons) of miniature form, or for that matter, form at all, for that matter, the final programme offered a fantastic anthology of miniatures, the large majority of which were convincing “single movement” and “closed form” miniatures, typically with very “reductive compositional ideas”, of a very “short duration” and “lacking development” of the kind that would befit a longer work.

Towards a Definition of Minature Form

As the comparative overview in the previous section has shown, despite the many interesting projects featuring various types of “works of short duration” and the exposure this has provide to an impressive number of composers, there is great discrepancy in regards to the understanding of what exactly constitutes a “miniature”, a “short work” or an “electro-clip”, and moreover, what distinguishes one from the other. And in many cases, composers and organizations alike seem to have appropriated these terms — poorly defined from the start, if at all — with a confidence that suggests they felt they had been common currency for so long and were understood so universally that it wasn’t necessary to clarify or justify their own use of the terms.

Ceci n’est pas une miniature; or, No Need for a Definition?

In some of the projects discussed above, only vague or arbitrary definitions of the musical form used as their basis were offered; in some cases no definition could be found at all. The New York Miniaturist Ensemble’s call for works declared a maximum 100 notes as the limiting factor, but did not explain what a “note” is. The Chicago Miniaturist Ensemble took on the idea of the New York group and also did not define what a “note” was, offering more questions on the subject in lieu of an answer. The Bozzini quartet’s miniature project had an interface that could be used to support the composition of a 50-minute work or longer. Several projects used the term “miniature” only in passing and/or without ever defining what a miniature was.

The pieces that were included in these and other projects dedicated to miniatures, electro clips or other kinds of works of short duration may indeed be of great interest musically, sonically, æsthetically, but the generally passive use of the term by the majority of the organizers and the composers involved has done little or nothing to further the understanding and definition of miniature form. But perhaps there was really no urgent need to define the miniature, electro-clip or short work beyond a possibly arbitrary choice of duration. The main interest of some of these projects had little to do with musical form or æsthetics of the individual works; rather they were primarily guided by promotional, programmatic and pragmatic considerations.

The discussion about the nature and delineation of miniature form has not, however, been as non-existent as the critique presented here makes it sound. The topic has in fact been discussed on various occasions in forums such as the <cec-conference> listserv, as well as in numerous private discussions with a wide range of individuals. However, these discussions have, in my own experience, largely taken duration as the starting point and remained the central factor around which the discussion obsessively revolved. The justification of one or another duration as the determining factor of miniature form was often explained in a fairly subjective manner; each person experiences specific durations in a different way, and this “problem” is exacerbated when the same person experiences the same work in different contexts (concert hall, home audio system, listening and discussion session amongst colleagues, in the car while driving to work…).

Ultimately, however, such discussions have been largely inconclusive. Part of the reason for this is that they have been essentially lacking in one key aspect — they were not supported by and did not make reference to an existing body of works that served to provide convincing musical and æsthetic representatives of the various manifestations of miniature form!

Alternate Versions of Existing Works

There seems to be no shortage of composers who have no compositional or æsthetic issues so strong that they would not truncate one of their compositions in order to fit the eligibility criteria of a call for works or a competition. For example, in the 2007 edition of the Concurso, there are several pieces that can be confirmed to be excerpts or alternate versions of significantly longer forms: David Berezan’s Hannibal (10:55; 3:48 version), Gilles Gobeil’s Entre les deux rives du printemps (18:08; 3:56 version) and Thierry Gauthier’s [pjanistik] (11:07; 4:56 version). Julio Shalom’s Cariño onomatopéyico (4:23) is an excerpt of a longer work entitled Tragedia y cariño onomatopéyico (9:28), itself one of a set of four miniatures.

A notable example of the inverse process, i.e. a piece that first existed as a miniature and was tailored upwards in duration, is Adam Basanta’s a glass is not a glass, which exists in no less than four different versions. The original “miniature” (0:60) was composed for submission to the 60x60 project in 2009, and in the process, the composer became interested in further developing the piece and so began to work on a longer version of the piece immediately thereafter. The end result, the “full piece”, was an 11-movement work (18:55) that was awarded 2nd Prize in the CEC’s Jeu de temps / Times Play 2010. There were also interim versions of the work: a five-minute “miniature” (5:00, movements I-III of the full work) that won 1st Prize in the 2009 Concurso, which was followed by a still longer work (9:45, I-VI) that was awarded 1st prize in the Student category of Métamorphoses 2010. The composer considers that the two longer versions are no longer miniatures, but rather works that are “formally structured [as] a series of musical tableaux” (Basanta 2013).

By tailoring their compositions (downwards in particular) to make them fit the eligibility criteria of a particular project or competition, composers have reinforced the negligent understanding of various issues surrounding miniature form. And in most cases, composers have not included the shorter “alternate” versions of their compositions in their works list! Does this not suggest that the composers themselves do not consider these alternate versions to be “complete works” fit for public presentation?

Perhaps we are judging too harshly here; there may in fact be some solid æsthetic reasoning that would justify the existence of these alternate versions — independent of the context for which they were adapted — that simply hasn’t been made public. The goal, however, of the present article is to clearly define the nature of the miniature form and its various manifestations. It is therefore fully acceptable for our present needs to question the tailoring of an existing piece to fit the criteria of a programme or competition of miniatures, electro clips or other, as such practices contribute little, if anything, to a clearer understanding of what a miniature actually is. Whether these alternate pieces stand convincingly as miniatures would an interesting and certainly relevant discussion. This we leave to be explored in some other more appropriate context, where contributions by the composers themselves (programme notes, texts and private correspondence) could be included in order to consider to what extent their practical intentions correspond in fact to a convincing æsthetic result.

Typology of Miniature Form

The reasons behind the choice of a particular duration as a determining factor for the definition of a miniature have arisen largely out of pragmatic considerations. In my experience, not one person or project has stood out as being able to explain in a convincing manner the way by which duration actually contributes to the definition of the work as a miniature. In fact few, if any, have even attempted a definition beyond vague choices of duration — under 3 minutes, approximately under 5 minutes — without coming to any decisive conclusions as to how the chosen duration impacts or defines the miniature form. While there has been some agreement on two possibilities for the limitation of a miniature (3 or 5 minutes), there has not been any real consensus on a more profound reasoning why either of these durations would be appropriate as a delimiting factor in miniature form.

Criteria

If we accept that duration as a determining factor in miniature form does not work in a convincing manner (partly because of the huge range of discrepancies in duration used as a benchmark), we need to consider what other factors could possibly determine a piece as a miniature — as opposed to a "work of short duration" or a single tableau forming part of a larger work. These factors could be, for example, the specific manner by which a given piece articulates, derives or generates form using its materials (sound, rhythmic characteristics) and gestures (movement, trajectories).

Already in existing “works of short duration” the level of complexity of the form and the range of materials encountered can often be seen to be somewhat constrained; the nature of the constraints specific to miniature form will necessarily be even more reductive. In order to determine — beyond the classic limiter of duration — whether a composition is a miniature or not, a few basic principles will need to be laid out as a framework. To this end, a work can be considered a miniature if it is understood to have most or all of the following characteristics:

- It is in many cases characterized by a singular and reductive compositional idea (in the sense of scope; it could in fact be quite complex sonically or musically);

- It lacks development of the kind that would necessitate or benefit from a large-scale form;

- It has a relatively short duration (typically under approx. 5 min.);

- In the large majority of cases it is a single “movement" form (which may also be further subdivided into sections);

- It is a “closed” form and does not seem to require continuation.

These criteria are proposed as the foundation upon which the typology of miniature form proposed in the next section is based. Several models are described, each of which can be expected to display the basic principles of the broader category of miniature form. It is important to emphasize that all of the five characteristics of miniature form must not necessarily be present (at all times) in the piece. Nor should composers feel obliged to slavishly follow the “rules” if they wish to call their work a miniature: these criteria are intended as guidelines, not dogma. For example, in regards to duration — the traditional indicator of miniature form — we will see below that some flexibility is needed in the context of some works in specific categories.

Categories

The categories of form proposed here are not necessarily restricted to use in miniature form. Larger works may use some of the models here as entire, enclosed sections, or as individual layers within the composition, but in such cases the section would not typically be able to stand on its own as a “closed” work, as should be expected of the miniature. The miniature that exhibits one (or more) of these forms will typically be a one-movement, closed form with a more focussed compositional idea and more restrained development than its equivalent in a longer form and duration. The individual categories and subcategories forming this list will be defined in more detail in the next section.

- Traditional Forms, or Works of Short Duration

- Étude de l’objet (Study of the Object)

- sound source or sound object;

- texture;

- rhythmic cell or meter;

- technique.

- Process Forms

- algorithmic;

- closed system;

- situational;

- teleological.

- Narrative Forms

- soundscape or soundwalk;

- anecdote, short story or text;

- “inner world”;

- cinematic or imagery.

- Snapshot Form

- Action Form

The first four categories in the list (traditional, étude de l’objet, process and narrative forms) and their subcategories have been established as viable miniature forms based on a reading of a large number of existing pieces, from the projects described above and many other individual pieces the author came across while attempting to establish the list of categories. The last two in the list, the “snapshot” and “action” miniature forms, are proposed by the author as further forms that would seem to be relevant to miniature form.

Definitions

Each of the categories and subcategories established in this typology are described in this section. In the next section, these are is illustrated with at least one audio example of an electroacoustic or instrumental work per category.

We will see through the examples that one category in particular, the process miniature, can in fact have a significantly longer duration than three to five minutes and still be considered a miniature. This is possibly also the case for the textural étude. Such considerations very naturally lead into reflections on the relationship between the miniature, minimalism and concept works; however, that is a complex discussion that would best be addressed in another dedicated context.

Traditional Forms, or Works of Short Duration

Many works having a short duration might more aptly be deemed short works rather than miniatures, as they display indisputable correspondences to one or another form type already established by larger scale compositions. Using the term “miniature” to refer to a work of shorter duration is a qualitatively different declaration than referring to it as “a short work”, or even a “work of limited duration”. Accordingly, for a short musical work to be considered a “miniature” — as opposed to “a short composition”, a “pop format” or “radio format” work, for example — it will need to conform to certain basic criteria, independent of the work’s duration.

In the miniature traditional form, the compositional scope, the phrasing and spacing, and the timing and temporal flow of the piece are noticeably different from works having longer durations. The musical ideas are dealt with in a more succinct manner and the breadth of the gestures is more restrained. A work in a traditional form can be considered a miniature when it engages the listener in a particular quality of listening or artistic experience — known or unbeknownst to its creator — that is fundamentally different than that encountered in larger scale works. The result, despite its short duration, provides a fulfilling, coherent and complete artistic experience, and does not leave the listener with the impression that “something is missing”, or that the work is incomplete. There is no specific durational threshold that can be stated which distinguishes a miniature traditional form from a work of short duration. It must be judged using criteria related to the composer’s musical intention and the listener’s actual perception of the piece.

Étude de l’objet (Study of the Object)

In the étude de l’objet category, the interest is placed on a single “material”, the object which constitutes the primary focus of the piece. The object that is examined, explored, developed, presented and represented can be a sound source or sound type, a rhythmic motif or characteristic, a sonic texture or a performance technique. The crucial point is that throughout the entire work the object in question maintains a strong presence and typically remains clearly in the foreground of the work. It should also be noted that today the didactic aspect of the étude is not nearly as significant (if at all present) as is often found in études from the 19th and early 20th century.

Sound Object Étude

The “object” in the sound object étude de l’objet is an individual sound or a sound type that is “put under the microscope” and examined in a detailed and intimate manner. A multitude of versions of the object — in the form of composed or processed variations of the original, or many different versions or recordings of the same type of source — are used as the only, or at least principal, sonic or musical materials in the work. There may be a high degree of variety in the variations or an obsessive focus on variations that closely resemble the “original”, but ultimately the exploration is more compact and intense in a miniature than it would be in a more large-scale exploration of the object.

Textural Étude

Characterizing the textural étude de l’objet is a more or less sustained sound or texture that may consist of a single, sustained element (a “chord”, a sound or a sound mass), or may be made up of multiple elements that complement each other in what could be termed “material polyphony”. In the case of a multi-layered sound mass, one of the layers may function as a foundation and be more present and continuous than the other layer(s), which may appear only periodically or may also be continuously present throughout the piece. The texture overall may be static and undergo little variation over the course of the piece, it may continuously morph into something new but with no clearly discernable direction, or it may evolve in such a manner that it is possible to predict to a degree the direction it will take.

Because it may in some cases lack a decisive dramaturgical direction, the textural étude may not always give the impression of being a “closed form”; it could in such cases be significantly extended or reduced in duration without fundamentally compromising its correspondence to the étude de l’objet miniature form.

Rhythmic Étude

In the rhythmic étude de l’objet, the focus is on a rhythmic fragment, cell, figure or motif that characterizes the piece, very often using simple meters or rhythmic cells with variations that remain quite close to the original source. This type of étude is easily recognizable when the exploration is obsessively concentrated on a singular element, but the rhythmic object can also be very abstract and/or irregular and not necessarily perceptible as a motif or cell; in the latter, we might consider rhythmic character rather than a rhythmic figure or motif as the object.

Technical Étude

This form essentially corresponds to the traditional étude we are familiar with from the 19th and early 20th century. A specific and very often singular technique on an instrument is explored almost obsessively and typically in an extremely virtuosic manner. This does not mean the piece is a mere display of the musician’s technical prowess on the instrument, but rather that the musical character of the piece is so intimately bound to the nature of the physical challenges inherent to the technique that it might be impossible to achieve the same musical results in an “easier” manner.

The use of the term “technique” in the electroacoustic domain is probably not relevant to this category, as a composer’s technique is normally subsumed in and an inseparable part of the compositional process and is not itself exploited as a sonic or musical material or process.

Process Forms

In the process miniature form, there is a system that is composed or programmed in advance that is responsible for generating or controlling in some manner the entire piece, or many aspects of it. The process itself is very often extremely simple, although the sonic and musical results may in fact be quite complex. It is also possible that the timeframe of the work — particularly for the teleological miniature — is defined only vaguely… if at all. However, because the character of such works typically corresponds so closely to the other “rules”, this form may extend far beyond the suggested timeframe (typically under approx. 5 min.) and still be considered a miniature. The process may or may not be perceived by the listener but is nonetheless understood as the singular defining factor of the piece.

This particular category inevitably — and justifiably — provokes questions concerning the similarities and differences between miniature form and minimalist and concept works. However, for the present needs, we will restrain from entering into a discussion that often evolves into something that is as open-ended and inconclusive as some of the works belonging to this category.

Algorithmic Process

The algorithmic miniature is the result of running a (simple) set of rules to produce the work, typically with the assistance of a computer; the actual output may in extreme cases be unforeseeable even to the composer. For generative miniatures, different runs of the same system may produce a work which “sounds” the same to the listener, or different versions may only resemble each other in some aspects, or there may be little resemblance apparent to the listener at all, depending on the rigidity or flexibility built into the code or language used to generate the piece.

While algorithmic music is already a widespread category of music creation, for the miniature we are more concerned with less expansive systems, preferring those that are more rigidly limited in their scope in terms of the compositional vista generated or the “program complexity” of the rule base.

Closed System Process

The scope — and possibly the form itself — of the closed system miniature is determined and/or limited by a set of compositional rules that forcibly restrict the output to the minimum “complete set” that can be defined, generated or exposed by the rules. For example, once all possible combinations and/or sequences of elements that can be extracted from a given set of sounds have been used once, the piece is complete; the exposition of all imaginable permutations of their ordering could also be determined via the same system. The materials themselves might also be determined by a similar (or alternate) application of the “rules” of the system. Other sonic or musical elements than those defined by the system, or regulated through its application, may be present, but these will not, generally, have anywhere near the impact on the nature of the piece as the system itself.

Situational Process

The situational miniature is defined — in part or wholly — by the inherent mechanical or physical limitations of a single event, or a small number of more or less parallel events, the duration of which may not be controllable through human intervention. Although in some ways similar to the closed system miniature — particularly in its self-contained nature — the situational miniature has a concrete human-scale (and possibly teleological) dramaturgy, in contrast to the abstract compositional dramaturgy of the closed system. The sound materials are extremely restricted and are tightly connected to the actual situation that is featured. The resulting temporal and sonic flow is natural to the event or situation; this form may therefore seem to be less “composed” than it is “exposed”.

Teleological Process

A clearly perceptible trajectory, or directionality, is the defining characteristic of the teleological miniature. It may not constitute the entire piece, but the process is perceived as a major contributing factor to a significant portion of the piece. The process may be closed or open, i.e. it is conclusive and can be heard in its entirety, or the piece could end at a given point either for compositional reasons or because of inherent physical limitations. The sound materials in the piece may evolve continuously over the course of the piece, or they may be accumulative or decumulative, becoming increasingly or decreasingly dense and complex.

Narrative Forms

In the narrative miniature form, the sound is generally meant to underscore, support or even reflect or represent the dramaturgical content and flow or development of some form of narrative. The narrative does not have to be based on or around a story (composed or orally transmitted) or a sequence of events that can be represented in a text form — it can also be a concrete or abstract exposition (or a combination of the two) of the sonic characteristics and identity of a place, or an existing or fictional environment; the narrative could even be the representation of an emotional or psychological state (of mind).

Soundscape or Soundwalk Narrative

Many soundscape or soundwalk compositions are inherently narrative simply by virtue of the fact that composers working in the genre often use extended, unedited passages of their field recordings as a foundational layer in the composition. Abstract sound that does not so clearly refer to a specific time and place as the unedited field recordings may also be added, but these are typically used to reinforce or enrich the inherent narrative character of the foundation. Even when such a field recording is not the principal layer in the work, or when more shorter excerpts are used of the field recordings than long, uninterrupted passages, by maintaining even a portion of the actual locational trajectory of the recording process, the composer imbues the composition with the “narrative” of his or her discovery or experience of the lieu or situation that was recorded.

Anecdotal or Short Story Narrative, or Narrative Built around a Text

In contrast to more expansive works using text or storyline narratives, the texts or stories used in miniature narrative form are usually concentrated on or around a single subject — an event, situation or character, for example. The subject may of course be part of a larger, more complex story but is treated here as a complete thing in and of itself, and the degree of its development is significantly limited in comparison to that which might characterize more substantial text-based works. It is quite common that the dramatic structure is largely to entirely defined by the tempo and flow of the text. The narrative could be traditional and linear, or it may be fragmented and not representative of the kind of real-time temporal contour that exists in “real life”.

Non-vocal or non-text sounds used in the piece may indeed reflect and support some aspect of the text but they may at times seem to be completely unrelated, where the sound almost has an abstracted soundtrack function. The text could also be sonified to some extent in the compositional process or via electronic processing of the text or vocal recordings. Sounds used in the presence of any text, vocal or spoken elements will very often — but not always — be notably less complex than in passages where the text is absent, for the obvious reason of textual clarity.

“Inner World" Narrative

For want of a better term, the inner world narrative is a sonic and dramaturgical representation of an emotional or psychological state, often that of the composer. The work is therefore highly subjective and can be extremely personal, possibly provoking some discomfort in the listener because of its intimacy. As emotional and psychological states are difficult, if not impossible, to truly represent purely by means of abstract sound (despite many arguments to the contrary), it is possible that a voice or vocal recordings are used in the piece to some degree. The meaning of the spoken words or vocalized text, the tension and emotion in the voice, and finally even the programme notes can then help listeners orient themselves in what might otherwise be so personal that few other than the composer could possibly perceive them from the perspective of the sound and composition alone.

Cinematic or Imagery Narrative

The cinematic or imagery miniature is an abstracted representation of locational situations and temporal spaces that may exist (separately or together) in reality, are extracted from other art forms, or only exist in the mind of the composer or listener. 9 (#9)[9. There may of course be a discrepancy between what the composer intends and what the listener perceives, as each person experiences the work as an individual and personal sonic journey. Again, this is in contrast to the soundscape, which intends to represent a concrete time and place.] The qualitative distinction between cinematic and soundscape composition is that the latter is to a large extent characterized by the representation of a specific environment in a given timeframe, both of which are concrete, existing and knowable.

This category includes, but is not restricted to, cinéma pour l’oreille 10 (#10)[10. The term “cinéma pour l’oreille” was originally used to advocate and explain the practice of composing with sounds that the listener, upon audition of the finished work, could not necessarily attribute to a specific source. Reference to the original instrument or object that produced the sound could be masked, obscured or erased altogether in the compositional process. It was not, however, solely an apologetic designation intended to explain the lack of perceptible connotative or programmatic structure in a work; the term provided a poetic locution for an emerging practice (eventually encompassing a range of genres) using a new medium that differed markedly from the bulk of the body of instrumental works being created in the same period. As the practice matured, composers would also exploit the connotative identity of the source in such a manner that not only the identity of the source, but also the listener’s understanding of the nature of its original context contributed positively to the dramaturgical evolution of individual compositions.] and related practices, for example, the representation in sound of an existing literary or cinematic work, however “authentic” the representation. Programmatic works that are abstract renditions of connotative situations that may or may not actually exist prior to the composition of the work also belong to this category. The cinematic narrative is in some ways similar to the inner world narrative, but with a dramaturgy that is based in either non-emotional situations or recreations of real or imagined spaces or stories. The experience of the listener may be quite different from that of the composer, but this is not in conflict with the form, as long as the work provokes associations with imagery in the listener; it could suggest scenes, characters and possibly dramatic flow and scenography that the listener integrates seamlessly into their perception of the work.

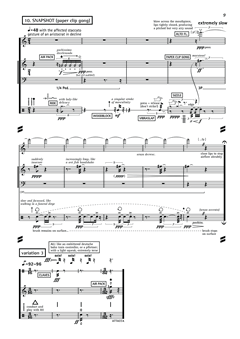

Snapshot Form

The foundation of a proposition for this new miniature form is an abstraction of basic photographic principles and their transposition into the domain of sound. The “subject” in the snapshot miniature is a singular sound or performative object that is “framed", “cropped” and given “perspective” and “depth” through its encounter, confrontation and exchange with other sounds, fragments, sound objects. In contrast to the étude de l’objet, here the subject appears only once, in its original form; if repeated, each reiteration will be “identical” to the first, again distinguishing the snapshot from the étude form, in which the subject is exhibited in diversiform renditions.

The casual, rough positioning of a subject within a heteroclite sonic environment is an attempt to replicate the spontaneous character of a photographic snapshot “taken from the hip”, without the self-conscious deliberation of a formal, composed shot. The establishment of the subject as the perceived focal point of the snapshot miniature is achieved not through volume (intensity), duration or recurrence of its presence, or even its central foreground position, but rather through the singularity of its character. For example, the subject could be a found object, an Alltagsobjekt (commonplace or everyday object) or a quirky performance technique; while it might be somewhat limited in terms of purely sonic or gestural potential, the subject is nonetheless of great musical interest in context… at least to the composer.

Action Form

A further and final addition to the miniature form typology, the action miniature is presumably restricted to instrumental music, due to its inherent visual nature. The musicians make use of various sound objects (in the sense of physical objects selected for their intrinsic sound-producing potential) in the performance of the work, complementing or even entirely replacing their instrument as sound- and music-producing objects. Where an instrument is indeed used, the musician will typically perform a variety of existing and new “extended techniques” 11 (#11)[11. An unfortunately polarizing term, it is now so ubiquitous that we must perhaps resign ourselves to retaining it as part of the vocabulary of New Music.] on it — their use is in fact problematized, instead of simply being integrated into the existing panoply of New Music performance techniques, as is typically the case with so many works using so-called “extended techniques”. Despite a conspicuous amount of “action” (physical movement) made by the performer(s) during the performance, a visual or theatrical dramaturgy may or may not in fact be evident. However, seeing the actions performed live is indispensible to the experience of the work, as the sense of the sonic result is virtually inseparable from the physical act of its performance. This is in stark contrast to the idea that a sound object (in the Schaefferian sense) can be perceived and appreciated as “pure sound”, divorced from and without a clearly perceptible reference to its source.

Examples

The works used in this section to illustrate the various categories and subcategories of miniature form have been chosen primarily for the clarity with which they articulate a particular miniature form type. Some of these may be characterized by more than one form type, but one of these forms can be clearly distinguished as a dominant characteristic. Inevitably, certain works or artistic projects that are perhaps terribly relevant to the establishment of a typology of miniature form may not be included amongst the examples. The purpose here is to illustrate the categories and subcategories with utmost clarity and concision. Such a project is necessarily reductive and selective.

Traditional Forms, or Works of Short Duration

jef chippewa — DUO (1998)

With its fairly “short duration”, this work fits the traditional criteria for miniature form, but we could easily imagine it with a longer duration. There are several divisional phrases that compromise any attempt to understand the piece as being a “single-movement” form. Despite the virtually exclusive presence of saxophone and modular analogue synthesizer materials, the nature of these materials and their use is so diverse that the piece is hardly characterized by a “singular and reductive compositional idea”, and the “development” of materials and structure is far too rich to correspond to our new definition of miniature form. Finally, the closure is convincing and leaves the listener with a kind of “almost satisfied” feeling, but perhaps not quite enough to consider it a “closed form”. 12 (#12)[12. Over the years, several people have disagreed with my feeling of closure, but I was in any case not concerned with creating a perfect cadential ending for the piece! It has been criticized for being “too short”: “The listener wants more!”; however, most agree that the materials explored here are not the kind you would want to be subjected to for more than a few minutes. From this perspective, I would suggest that maybe it might not feel “finished” but it is certainly “enough”. I have in fact always felt this to be a perfect length for the piece.]

Gilles Gobeil — Nous sommes heureux de… (1992)

Many of Gobeil’s works are characterized by musical phrases that are very conclusive but ultimately part of a more large-scale form. This particular piece would seem in some ways to be an excellent example of miniature form, but its two-part structure is not very conclusive. To suggest the piece almost seems like the opening section to a larger work by the composer is not so far off the truth: many of the individual elements here are in fact excerpted from Gobeil’s larger works. A more convincing “single movement” (albeit two-part) and “closed form” miniature by the composer is Associations libres (1990 / 3:08).

Étude de l’objet

Sound Object Étude

Hugh Le Caine — Dripsody: An Étude for Variable Speed Recorder (1955)

The entire work is composed using variations of a single sound source — a drop of water. Multiple versions of the water drop were re-recorded at different speeds using a custom multi-track recorder built by Le Caine himself, the Special Purpose Tape Recorder. The different recordings were then used to create this rhythmic, pentatonic electronic work.

Andrew Lewis — Tantana (2013)

The original field recording used as the sole source for this piece was subjected to very little variation or transformation, but there is already an intensely concentrated focus on a limited range of sound materials in the recording itself. The composer was in Freiburg (Germany) during the Euro 2008 and on the evening he made the recording, “Turkey had beaten Croatia in the quarter finals, and the numerous Turkish supporters in the city took to their cars to create their own improvised celebratory fanfares” (Lewis). “Tantana” is the Turkish word for fanfare, also a well known short musical form.

Textural Étude

Nathaniel Virgo —

{LocalOut.ar(a=CombN.ar(BPF.ar(LocalIn.ar(2)*7.5+Saw.ar([32,33],0.2),

2**LFNoise0.kr(4/3,4)*300,0.1).distort,2,2,40));a}.play//#supercollider (2009)

Three elements remain present throughout this work, each rhythmically independent of the others yet sonically linked. There are two types of rhythmic variation, but as a whole, nothing really “changes” in the piece. Algorithmically generated, it could go on forever.

Rhythmic Étude

Javier Álvarez — Mambo à la Bracque (1990)

At the heart of this piece is an obsessive exploration of snippets from various recordings of a famous mambo tune, which are contrasted with sounds created by the composer. The mambo feel is present throughout, even though it is extremely fragmented and refuses to hold together as an actual mambo, in the sense of a piece one could actually dance to without drawing strange looks…

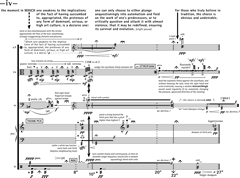

jef chippewa — 17 miniatures (2012 / 25:00): 04. reiterations

for flute, extended piano, drumset and dozens of sound-producing objects

Eight variations on a simple figure consisting of five reiterations of an individual sound in an extreme deceleration are played in parallel and form the large majority of the piece (Figs. 2a-2b). All of the variations start pppp and half of them (claves, snare drum, heavily dampened piano, picked piano string) crescendo to as loud as possible, while the others (triangle, ride, bass drum, piano harmonic) remain at pppp throughout. This results in a transition from a thick, multi-sound texture (all at pppp) to a sparse texture of individual sounds (at either pppp or ffff ). 13 (#13)[13. The last attack of the ride appears in the next piece; the last dampened piano note was omitted for compositional reasons.]

Technical Étude

Salvatore Sciarrino — 6 Capricci (1976 / 18:00): I. Vivace (1:22)

for solo violin

An obvious homage to Paganini’s 24 Caprices (1819), Sciarrino retains both the virtuosic character and the rapid ricochet-arpeggiated passages in his own first movement, but replaces Paganini’s tonal harmonic structure with an exploration of natural harmonic arpeggios. These are interspersed with “normal” notes as well as notes played as harmonics at positions where no natural harmonic exists, producing ephemeral “noise” sounds in the midst of the brilliant harmonic sounds.

Process Forms

Algorithmic Process

LFSaw — {Splay.ar(Ringz.ar(Impulse.ar([2, 1, 4], [0.1, 0.11, 0.12]), [0.1, 0.1, 0.5])) * EnvGen.kr(Env([1, 1, 0], [120, 10]), doneAction: 2)}.play (2009 / dur. undefined)

All of the SC140 works could be considered to fall in the algorithmic process category. The title is in fact the code that can be used to generate the piece using the software SuperCollider; the only “rule” was that the title/code had to be short enough to send as one 140-character (or less) Twitter post. Paraphrasing Malcolm McClaren: “The code is the piece.”

Closed System Process

jef chippewa — 17 miniatures (2012 / 25:00): 17. chord

for flute, extended piano, drumset and dozens of sound-producing objects

Each of the three musicians plays only two sounds (with a couple of anomalies) in the entire final section of this work 14 (#14)[14. As might be expected, given its title and the fact that the author of this text is also the composer, many of the categories described here can be found in this work.]: one percussive or dampened sound, and one sound with a clear sustain after its attack. Each musician plays only one of their sounds in each group of three attacks, forming “arpeggiated chord” subsets of the full six-sound palette. Once all the “arpeggios” that can be extracted from this set — e.g., 1a-2a-3a; 1a-2a-3b; … 1b-2a-3a; 1b-3a-2a; … 3b-2b-1b — have appeared once, the piece is over. 15 (#15)[15. This final section of the work is an alternate reading of the same process in the second section. Although the order of the permutations used in these two pieces was derived in part by chance operations, if the order was deemed to be unsuitable to the type of dramaturgy desired, it was discarded and a new order generated until a suitable one was found to work in both pieces.]

Situational Process

Bernhard Gál — this is for real (2004)

In its simplicity and wit, this is an almost Fluxus-like exposition of what is for most a fairly uneventful — even banal — yet desperately intimate everyday act. This particular human-scale event not only functions as a limiting factor in terms of the sonic and rhythmic character of the piece, not to mention its duration, but also defines the contours and (er…) “flow” of the dramaturgy. With a coda.

The source material is a recording of a male subject urinating in a toilet, shaking out the last drops of urine and finally, after a short pause, flushing the toilet. The recording was time-stretched to fit the duration requirements of the CD project it appears on as well as to play with the project’s concept and title: “90 seconds of reality”. While we could imagine different versions of the piece, with different “performers” who drink varying amounts of liquids beforehand and/or control the “output” to various degrees, ultimately their form and dramaturgy would still be strictly circumscribed by the same category of human-scale physicality.

jef chippewa — in nomine (2004 / 5:00): iii

for flute, oboe, clarinet, piano, percussion, violin, viola and cello

The durations in the last part of the final section of in nomine are defined by the inherent limitations of some of the sound objects and instruments: the duration of the sustained chord is “as long as the oboist can hold the note” (without recourse to circular breathing); the flutist grates one entire carrot rapidly while the pianist cuts out (individually) all the letters of the alphabet written on a large sheet of thick construction paper. Each of the materials is “finished” when it is no longer physically possible to make it sound.

Teleological Process

Alexander Grebtschenko — < (2003 / ca. 11:00)

for tape and ca. 10 (different) small loudspeakers

The “tape part” for “>” 16 (#16)[16. The title is pronounced “kleiner als” (less than)] is an extremely dense mix of various heavy metal pieces 17 (#17)[17. Arguably, the would work just as well using a mix built of excerpts taken from Classical string quartets or from Beethoven symphonies, or “Balalaika Choir, or whatever” (Grebtschenko).] that is sent in mono to all loudspeakers at an equal level. The faders are at infinity at the beginning and are all brought up very slowly over the course of the piece. Gradually, each of the speakers begins to distort and eventually the speaker cones rip — individually, due to the different qualities of the speakers. At the end, the speakers produce nothing but noise that only vaguely resembles the sound materials actually recorded on the tape.

The response of the individual speakers along the trajectory of their destruction is unique, so the actual sonic output of the piece and local rhythmic characteristics at any given moment are impossible to predict, although the general characteristics of the sound mass and the general contour of the piece are easy to foresee. In many pieces with a teleological process, the sonic trajectory or directionality of the piece could just as easily be reversed, or stopped when the composer chooses — and this is particularly true of electroacoustic pieces. However, with Grebtschenko’s piece, the process is in fact irreversible.

Panayiotis Kokoras — Magic Piano (2013)

The teleological process articulated over the entirety of this work is a compositional directionality, and could conceivably be reversed, unlike the physical irreversibility of the teleological process in Grebtschenko’s work. The accumulative gesture is a very convincing trajectory that “pushes forward” in a singular direction and with exponentially increasing weight before breaking, forever changed, into a new state. The materials and sonic character at the end of the piece are reminiscent of those at the start, but exist in a very different time and space, compositionally speaking.

Narrative Forms

Soundscape or Soundwalk Narrative

Émilie Payeur — Paysage automatique (2010)

The narrative character and gestural flow of this piece are tightly regulated by the rhythmic qualities and “tempo” inherent in the field recordings present throughout the work. Even when more abstract elements or electronically generated sounds appear, or when portions of the recording are heavily processed, their influence is undeniable. This half-fabricated soundscape is of an indefinable place, the identity of which the listener does not need to know. The footsteps in the field recordings give the piece a very strong sense of direction, which the composer has subverted in a “promenade surréaliste” that continually folds back on itself, creating an uncomfortable dream-like atmosphere in which we continually finds ourselves “back where we started”.

Egils Bebris — Hockey Night in Opera (1995)

The title of this work is playful combination of “opera” and the name of a Canadian sports show broadcasting in various forms since the 1930s, Hockey Night in Canada. By the 1970s, the weekly show had long been a virtual religious experience for sports fans in Canada and the northern USA: the Saturday Night Fever for the sports fan. The drama that unfolded on the TV screen each week caused emotions to run high, alliances to be made and broken, dreams to be built and shattered… much like in the opera. Bebris’ ode to sports and opera is a roller coaster soundwalk that vacillates between the opera hall and the hockey arena, exploring crowd reactions and sounds inherent to their respective temples rather than the actual “ceremonies” held therein.

Anecdotal Narrative

Wendy Atkinson — Summer BBQ (2006)

The musical accompaniment (eBow on electric bass, performed by the composer) is extremely minimal and meant to underscore — and not disturb! — the clarity of the spoken word narration, in which the composer recounts a sad occasion when a family dinner suddenly took a turn for the worse. Electronic manipulations of the voice serve the text directly, to create a polyphonic battery of demeaning commentary the composer’s mother received from her mother-in-law, a reflection of the mother’s emotional and psychological state at the moment when she had finally “had enough”.

Short Story Narrative

Steve Heimbecker — I Beat John Sobol at Pool Last Night (1995)

The composer narrates a story about playing three games of pool with a man named John Sobol while drinking beer and whiskey. Although the narrative character dominates when listening to this “Word Music” composition, the algorithmic process (knowledge-based system) used to generate its musical accompaniment is also an important determinant factor for the form: “the computer transcribes letters, words and sentences into musical notation which allows the author of any text to be the musical composer as well. The text is the music” (Heimbecker 1995).

Narrative Built around a Text

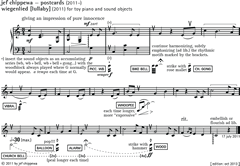

jef chippewa — 1+5 (2006 / 3:00): iv

for slam poet, alto flute, viola, cello, piano and drumset