Launch Concert for the Concordia Archival Project (CAP)

Launch of the Concordia Archival Project (CAP)

17 March 2009

Montréal, Canada: Black Box Theatre, Concordia University

https://cec.sonus.ca/education/archive

[Return to: Concordia Archival Project | eContact! 11.2 — Canadian Figures (2)]

The following pieces were selected from amongst around 3000 works which form a collection held at Concordia University (Montréal) that was the focus of the Concordia Archival Project (2007–08). From the works that had been digitised in the course of this project, a selection was made to fill a 50-minute concert programme that aimed to highlight the contributions of Canadian composers / sound artists in the collection and to reflect the stylistic and historic breadth found in this collection. The concert was an opportunity to hear works that were not necessarily part of the standard Canadian “electroacoustic canon” but were nonetheless considered to be important contributions to the development of an extremely diverse and inclusive community of practitioners in Canada.

The concert programme, presented now in this SONUS Gallery, is another excellent summary of the works found in the larger collection, and effectively shows the broad range of backgrounds and interests represented by the composers in the collection. The reader is encouraged to explore the various components of the Concordia Archival Project for additional ways to appreciate the works and composers in this vast collection:

Presentation of the Works in the Collection

A Media Library has been developed to present the works from the collection. Here you can find composer biographies and programme notes, and listen to works that have been digitized.

Educational modules present the history of electroacoustics in Canada and internationally, technical aspects of electroacoustics from various periods, and the process of restoring and archiving the collection. Using works from the collection as audio examples, these modules are ideal for classroom use as well as for self-learning.

eContact! 10.x — 10th Anniversary Special Issue: The Concordia Archival Project (CAP)

A special focus issue of eContact! featuring the Concordia Collection, with articles about archiving and preservation, and about other archives and collections. Several interviews with key Canadian figures and a CECG/GEC archive give insight into the development of the Canadian electroacoustic scene through the 1970s–80s.

The world’s largest freely available online jukebox for electroacoustics holds a subset of the works held in the collection.

Concert Programme

Works which were not played in concert (for reasons of time) are indicated with an asterix.

Daniel Feist — Auxferd Nightburr’d; November 2 AM (1984–85 / 1:00)

* Barbara Golden — Tripping to Greece (1980 / 9:45)

John Wells — Rock in the Water (1979 / 2:30)

Jill Bedoukian — Trenholme Park after Dark (1984 / 4:40)

Ricardo Dal Farra — Estudio Sobre Ritmo Y Espacio (1982 / 1:03)

István Anhalt — Electronic Composition No. 3 “Birds & Bells” (1960 / 11:00)

Kevin Austin — Sam McGee (Part II) (1970–73 / 9:00)

John A. Celona — Possible Orchestras (at the 21st harmonic) (1984 / 12:57)

* Ann Southam — The Reprieve (1975 / 26:08)

Daniel Feist — Our Child (1984–85 / 1:38)

Presentation of the Works in Concert

The works played in concert were introduced and discussed by Kevin Austin, relating the genesis of the collection and providing a narrative that contextualised the works within the larger movements and interest of the developing electroacoustic community at Concordia University, In Montréal, in Canada and internationally in the 1970s to the early 80s. The full audio from his talk is interspersed in the text below.

Click on the titles to open up a page with programme notes and where you can listen to the work.

Audio 1. Kevin Austin introduces the concert.

Daniel Feist — Auxferd Nightburr’d; November 2 AM (1984–85 / 1:00)

Hasn’t he heard

Nobody’s listening

This text-based piece, the first part of a diptych by Montreal radio personality / composer Daniel Feist, won the “public prize” in the ACREQ Electroclips competition. It speaks directly. combining text, sound and “music” in a non-temporal narrative, and is a commentary on the state of ea in the early 1980s, and about the future — it is our children’s future, not ours, which is why we must protect it.

* Barbara Golden — Tripping to Greece (1980 / 9:45)

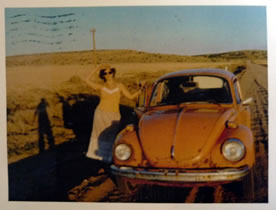

Barbara Golden somewhere in New Mexico on her way to Mills College, August 1979. Photo of a postcard.

Barbara Golden is one of the first non-traditional female, multi-disciplinary artists to emerge from Montreal, and 35 years later she is still doing ea, live performance, hosts Crack o’ Dawn on KPFA (Berkeley), paints, cooks, writes poetry, and plays in gamelan orchestras, among many other things. In this interpretive and quasi-auto-biographical work we find a union of memory, word and sound. It draws upon the Bohemian artistic temperament of authors such as Arthur Miller and Jack Kerouac, and Golden’s sound art pieces are another mode of expression of the captured moments and impressions. The text is straightforward, clear and has that Greek-blue luminosity, and commentary without the bullshit.

John Wells — Rock in the Water (1979 / 2:30)

Audio 2. Austin discusses Daniel Feist’s work, organizing concerts in the “early days” and the diverse backgrounds of those working in the Concordia studios.

John Wells could never get enough of the sounds. Photo © Michèle Gour.

John Wells came from a graphic arts, design and printing background before getting involved with electroacoustics. He “did sound” for theatre and dance, often employing direct, “naïve” elements, as in this composition. John also designed and printed the CECG/GEC posters for the first five or six years. There was always a fascination with the exploration of some kind of “small” idea, a new way of seeing, a revisioned way of hearing. As a performing member of the CECG/GEC ensemble for about five years, every time he “attacked” the Synthi, there was an energy flow in both directions — he was always totally engaged in what he was doing. Totally.

The works in the collection are not only of sonic and historical interest but also offer many insights into the changes and developments of the techniques and technologies used in electroacoustic creation, especially throughout the 1970s and 80s. CAP eLearning Module #2, “Guided Listening Tour”, provides a chronological narrative that discusses many of these changes, using audio examples from the collection as illustrations. Rock in the Water is referred to in the “Diverse Sources, Multitracked” section of the module as a reflection of the state of electroacoustics in the late 1970s:

The source recording is of the highest quality, the loops are subtly effected and the mixture of the voices is realized with finesse. [A] certain freedom in the compositional project can be felt that … is likely due to the ease with which the equipment can now be used but also perhaps due to the Zeitgeist, the general “spirit of the times”.

Jill Bedoukian — Trenholme Park after Dark (1984 / 4:40)

Audio 3. An introduction to Jill Bedoukian, who entered the studios in the days when soundscape was beginning to develop.

Bedoukian is a non-traditional (ex-)housewife who discovered that while the Montreal Symphony Orchestra had violins, ea was not (as was popularly believed), violence to the ears. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s there was a small but continuous flow of “adventurous women” who had heard about the new arts but by habituation had not had access to them — the technologies or the æsthetics. Of the two, the technology was clearly the more difficult to deal with and many of them partnered with others who could provide the “rapid access” to the technological aspects, allowing the composer / creator to focus more on the ideas. While the æsthetic character of this work is in some ways typical of broad urban soundscape, it also combines collage, sociology, a tribute to Charles Ives and:

distinguishes itself by the fact that it wavers between associative and non-associative references. This vacillation is the result of very subtle montage and mixing. Such manipulations bring the whole piece to a certain level of abstraction and engender a perceptual ambiguity from which a unique climate of foreignness emerges. (eLearning Module #2, “Diverse Sources, Multitracked”)

Ricardo Dal Farra — Estudio Sobre Ritmo Y Espacio (1982 / 1:03)

Audio 4. Austin describes some of the materials used in Bedoukian’s work and introduces Concordia Music Department’s current Chair, Ricardo Dal Farra.

Born in Argentina, composer Ricardo Dal Farra is currently the Chair of the Music Department at Concordia University in Montréal. He was the principal researcher in an archival project funded by the Daniel Langlois Foundation, focussed on the Latin American Electroacoustic Music Collection, a collection he started building in the 1970s (see summary in eContact! 10.x — CAP).

The form in very short electroacoustic works (30–90 seconds, let’s say) is necessarily simpler and even more blatant than the more drawn-out, “developmental” works more typical to electroacoustics (esp. acousmatic). There are a number of shorter works in the collection, or miniatures as some may prefer to call them, and they may varyingly be perceived as being a single sonic gesture (a “closed” or open-ended idea), texturally-based (static or teleological) or perhaps poetic (see Feist, above) or episodic in nature. Dal Farra’s stripped-down study for concrète sound with real-time computer processing offers an example of the effective and efficient use of an extremely limited sound and gestural palette. And — yikes! — a witty and humourous electroacoustic piece as well!

István Anhalt — Electronic Composition No. 3 "Birds & Bells" (1960 / 11:00)

Audio 5. Austin recounts his first experiences with Anhalt’s early electronic music work and some of the composer’s experiences at the end of the Second World War, experiences which are reflected in Electronic Composition No. 3, and describes what a 1960s electronic music studio would have looked like.

Electronic Composition No. 3 was a seminal work in Kevin Austin’s own development. He heard the piece 15 or more times in one afternoon in about 1968, saw lights and colours, and never turned back from a sonic future. It is also one of the few well-known large-scale works that employ some of Hugh Le Caine’s equipment so extensively. Here, the studio is the “instrument”.

This piece is unusual in that the composer had “the sounds” in his head fifteen years before the technology was available that would allow him to realize them. Also characteristic of the early days of electronic music, composers explored many aspects of sounds while learning the skills of the studio, with the objective of being as technically skilled in the studio as they were with the pencil. Anhalt discovered an analysis of the components of a bell in his readings, and at the same time knew Hugh Le Caine’s work with pure additive synthesis — the use of a bank of sinetone oscillators to (more or less) create any sound he wanted. The oscillators used in this piece were from decommissioned World War II bombers — the irony of Swords into Plowshares was not lost on survivors of the War who recognized the necessity of moving forward to provide the world with a brighter future. What could be a better celebration than birds and bells?

Kevin Austin — Sam McGee (Part II) (1970–73 / 9:00)

Audio 6. Austin gives an introduction to Sam McGee and explains how the piece came about, the technical setup and compositional approaches to composing the four movements of the work, and his early experiences working with live electronics in Montréal.

Kevin Austin performing Sam McGee, ca. 1973.

“An odd piece this,” offers Kevin Austin. While the first movement (19 minutes) took over a year to compose, and the third movement took about a year as well, this piece was composed in the studio in “almost” realtime. It is part of one of the first four-channel pieces composed in Canada, and quite possibly the first piece for four-channel tape and live electronics in Canada.

Part II of Sam McGee offers a bit of insight to the degree of sonic complexity that was already possible in a “live” setting controlled by a single person in the very early 1970s and this work would be the final stage in Austin’s transition to working in live electronics (esp. MetaMusic) through the 1970s. As might be expected, the textures are sometimes simple when compared to fully studio-composed works from the same era, or even to the first movement of this same piece. Notable here, however, is the composer’s control of the sonic gestures and temporal unfolding of the various complementary and contrapuntal (!) layers, not to mention of their individual and collective dynamic.

The degree of immediacy characteristic of live electronics that developed throughout the 1970s and into the 80s would be more or less lost with the arrival (or putsch?) of the digital era. Fortunately, over the past decade or so, many new tools have been developed which once again offer the electroacoustician a great degree of immediacy and complexity in live situations, and improvisation using electroacoustic means has once again become a fruitful area of exploration.

There are many aspects of homage and memory buried in this rather sprawling piece. It is a sort of homage to the important influences of Charles Ives for the invention of collage technique, and Stockhausen. The first and last movements are built on a cantus firmus of a reading of the poem, The Cremation of Sam McGee by the Canadian humorist / poet, Robert Service. The poem was read as a duet by Martin Gotfrit and Austin, and then this recording was processed in the same way as Alvin Lucier’s I am Sitting in a Room, exploring aspects of equipment and acoustical resonances in the distortion of the text.

The Third Movement is a complex, ten-minute, four-channel collage that is in eight layers, with no fragment in any channel lasting more than a few seconds. The instrumental / vocal elements (one layer in each speaker) are drawn as pre- and post-echoes from the work itself, some of the composer’s early instrumental compositions, fragments of Holst’s band music, and a hidden section from István Anhalt’s Symphony Number One. The first movement has a structure based around the introduction to a German march played by a “Bavarian” band which Austin had played in for five years, while the female voices in the same movement are taken from readings provided by friends and students.

Seen from a distance of over 35 years, Austin sees the last movement as an “explosion of [his] traditional values”. For some reason(s) Austin’s approach in the studio was “quite conservative”, and he explains that he:

tried to avoid producing ugly or distorted sounds, but after two years of working with MetaMusic, my sensibilities were much more prepared to accept distortion and ugly sounds, that had ceased to sound either ugly or distorted. I find the gestures of the second and fourth movements to be stronger than the carefully planned first and third movements, and attribute this slightly to the fact that the second movement was completed within hours — almost realtime — and the last movement was completed in about 4–6 weeks as I had to finish the piece in time for the first performance!

Kevin Austin gratefully acknowledges the continuing support of Martin Gotfrit throughout the sometimes difficult two and a half year journey required to complete this piece. The transfered tapes are not the originals (for technical reasons), but are low speed second and third generation dubs and a copy of a second performance in around 1980.

John A. Celona — Possible Orchestras (at the 21st harmonic) (1984 / 12:57)

Audio 7. The major revolution in the studios in the 1980s was due to the greater availability of technologies and would eventually lead to composers moving away from studios to build their own home studios. Austin also emphasizes the tremendous breadth of the types of works contained in the collection which CAP was concerned with.

Many different reasons exist for compositions; sometimes a composer is driven by inner forces, sometimes by outside forces. Sometimes it’s idle curiosity, and sometimes it is the existence of a new option to explore an idea that has been unrealized. The history of the DX-7 and digital FM is well-documented, but most histories are unable to capture the absolute “AH-HA!” characteristic of playing a note on the DX-7 for the first time in the early 1980s. Most electronic music composers had heard FM synthesis, mostly the generally low quality produced by modular synthesis systems — annoying after a short period, and, more likely, the gorgeous sounds produced on $300,000 computers that a handful of people had access to. Composers knew the theory; they had not had the experience.

Suddenly, for $2000 and some hard work, it was possible for the composer to “get inside” digital FM synthesis, and many who were not daunted by the real complexity of programming 160 parameters on a screen that showed two lines of text, found themselves in the wonderfully wacky world of FM complexes, multi-stage envelopes which were unrestricted by modular (and human) considerations, detunings and so much more.

Possible Orchestras is in the family of works produced by the speakerful in the early 1980s, some number of which are rather clearly surface-scratchings as the composer was unable to “crack” the complexity, and others, such as Celona and Thibault exerted the energy to produce both interesting and complex basic sounds, and the compositional acumen to place these sounds into larger compositions.

* Ann Southam — The Reprieve (1975 / 26:08)

Many of Ann Southam’s works for tape in the 1960s–70s and through the 1980s were composed as the musical component to modern dance works choreographed by Patricia Beatty (Toronto Dance Theatre) and other choreographers. She enjoyed working in the studio in “the early 60s, [when] electronic music was pretty much in its infancy,” for the freedom it offered to “set your own rules.” (“Ann Southam: If Only I Could Sing,” interview by Kalvos & Damian, eContact! 10.2 — Interviews (1) [August 2008]) The Reprieve was composed for a Beatty choreography and illustrates the freedom and “love of sound” Southam experienced in the studio: it is an exception to the “rule” that “Subtractive synthesis is inherently limited in its potential to create a rich palette of innovative sounds.” (eLearning Module #2, “Synthesis — Subtractive”)

Daniel Feist — Our Child (1984–85 / 1:38)

It’s not about us; it’s about the future, baby.

Audio 8. A few closing comments by Kevin Austin.

Thanks to Tim Sutton for preparing and providing the audio excerpts.

eContact! 11.2 — Figures canadiennes (2) / Canadian Figures (2). Montréal: Communauté électroacoustique canadienne / Canadian Electroacoustic Community, July 2009.

Produit avec le soutien financier du Ministère du Patrimoine Canadien

Produced with the financial participation of the Department of Canadian Heritage

Social top