Playing with the Voice and Blurring Boundaries in Hildegard Westerkamp’s “MotherVoiceTalk”

Our voice is our primary expressive instrument. We all recognize vocal sources and it is nearly impossible to disentangle vocal and human associations. The voice is an indicator of complex emotional states as well as a carrier for communication. (Collins and d’Escriván 2007, 239)

Because of the voice’s role as “primary expressive instrument”, composers and performers alike have been drawn to an exploration of its expressive possibilities on multiple levels. Twentieth-century performers pushed the limits of the voice’s expressivity through varied and often astounding extended vocal techniques. Sound poets challenged the equivalency of language and semantic meaning by using phonemes as abstract sound. Composers combined these elements (i.e., the expressive and the communicative) with the emerging electronic technology to further explore the limits to this potential of the voice.

Soundscape artist Hildegard Westerkamp (b. 1946) is one of many composers who seek out the æsthetic and creative elements of working with language in her numerous works that incorporate poetry, autobiographical narrations and articulated soundwalks. Westerkamp was an early and influential member of the Vancouver-based World Soundscape Project. Following undergraduate studies in music at the University of British Columbia (1972), Westerkamp worked as a research associate (1973–80) with R. Murray Schafer with the World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University. Her early work was influenced by the World Soundscape Project’s focus on noise and the acoustic environment, the possibilities of electronic technology in the studio, and avant-garde composers such as Pauline Oliveros and John Cage. Her interest in the human voice as a sound source has led to numerous works that include the voice: adults and children, talking, laughing and reading poetry. In addition, she often uses her works to reflect on her own experiences and beliefs. Both of these aspects are present in MotherVoiceTalk.

MotherVoiceTalk (2008) is a fifteen-minute work that examines Westerkamp’s affinity to Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994), a Japanese-Canadian artist and poet. Along with compositions by Jocelyn Morlock, Stefan Smulovitz and Stefan Udell, MotherVoiceTalk was commissioned by Vancouver New Music to engage with the artistic output of Kiyooka in a project entitled Marginalia, re-visioning Roy Kiyooka. 1[1. The other works presented at the concerts were Jocelyn Morlock’s Scribbling in the Margins (2008) for clarinet, percussion, string quartet and piano, Stefan Smulovitz’s Triptych K (2008) for cello and live processing, Stefan Udell’s Latticies of Summer (2007) for chamber ensemble including live electronics, and Kendrick James’ interspersed sound poetry.] It was premiered at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre on February 20, 2008. 2[2. Although the event was advertised from February 20–23, 2008, and Westerkamp identifies February 20, 2008 on her website as the premiere date for MotherVoiceTalk, in “An Imaginary Meeting,” she states the event took place three times: February 21–23, 2008. Westerkamp graciously shared this article with me after I emailed to request a copy of MotherVoiceTalk. Westerkamp’s article will be published as a chapter in The Art of Immersive Soundscapes, edited by Pauline Minevich, Ellen Waterman and James Harley (Regina: University of Regina Press, forthcoming).] The title of Westerkamp’s work refers to Kiyooka’s 1997 book Mothertalk, which sought to tell the stories of his mother, her family, her children and aspects of the Japanese immigrant identity. 3[3. Mothertalk was published three years after Kiyooka’s unexpected death in 1994.] MotherVoiceTalk contains sonic material consisting of excerpts from tapes that Roy Kiyooka made himself; these tapes include his spoken voice, his zither and recorder playing, and his mother Mary Kiyoshi Kiyooka’s voice. 4[4. The recordings from Mary’s voice are from interviews Kiyooka arranged between his mother and Matsuki Masutani. Kiyooka felt too insecure about his own Japanese proficiency to interview his mother directly.] In addition, Westerkamp includes the German-speaking voice of her own mother, Agnes Westerkamp.

In “An Imaginary Meeting: The Making of MotherVoiceTalk,” Westerkamp describes her approach to the piece: “My task as I perceived it, was to ‘listen’ to Kiyooka’s artistic and personal voices on all possible levels and bring them into dialogue with the musical, sonic tools of my own composition and personal voices” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 4). 5[5. Page numbers are from the document Westerkamp sent to me as an individual document, not the final page numbers in the book. The piece itself will be published alongside her forthcoming chapter in The Art of Immersive Soundscapes. A five-minute excerpt can be heard on Westerkamp’s website.] She explains her struggle to find connection to and inspiration from Roy Kiyooka, a person she never met, and from his varied output:

I wanted to find points of resonance with his work that would somehow enable and inspire me to find my way into a composition, to find its instruments and sonic materials. How would I transform my dialogue with his writings, visual arts, and musical/sonic improvisations into a sound piece? It is one thing to like or even to be passionate about another artist’s work. It is another to internalize his work to such an extent that his artistic inspiration and process can inform my own and vice-versa, that my compositional process can become the medium through which his voice and work is made audible and meaningful to the listener. I experienced this task as utterly enormous. (Ibid., 3)

In finding this resonance, MotherVoiceTalk negotiates three boundaries that are often blurred in the electroacoustic medium: public and private; self and other; and time and space.

Public vs. Private Space in a Recorded Medium

By blurring the boundaries between public and private, Westerkamp creates a unique “sense of place” in MotherVoiceTalk. The development of transportable recording equipment has contributed to the erasure of the boundary between public and private spaces. The soundscape of nature signifies a public space with (mostly) free and (relatively) easy access. Alternatively, the sounds of the home — of friends and family conversing, sharing life stories — signify a private space, where intimacy is a privilege granted or earned: access cannot be assumed. This blurring of public and private can become an essential mode of expression.

The conversations between mother and son and the imagined meeting of Westerkamp and Kiyooka are extended from the impermanent personal into the permanent public through transduction. Diffused in live performance, and distributed on compact disc, such personal sounds become public; yet they retain dual status as both public and private, for without the referential understanding of these sounds as private, the expressive power is lost. The intimacy of the private sounds is often highlighted through techniques such as close microphone placement. The presence of heavy reverb on the voice communicates distance to the listener, between him and the voice; a listener who is closer to a sound source will hear a larger proportion of direct sound than reverberate sound: close microphone placement ensures a high level of direct sound (Dibben 2009). This close microphone placement results in a “flat” voice, which is “close-up sound, sound spoken by someone close to me, but it is also sound spoken toward me rather than away from me. Sound with low reverb is sound that I am meant to hear, sound that is pronounced for me…” (Rick Altman 1992, 61; italics in original). In addition, manipulating certain aspects of the mix can result in sounds that “hear” close, particularly on the auditory horizon, and the vertical and horizontal planes. 6[6. Hodgson (2006) describes the mix as a way of hearing.]

Sounds can also extend from public to private. Westerkamp prioritizes soundscape elements, using them to signal both specific places (e.g., the Canadian west coast) and general spaces (e.g., a beach). It is in these general spaces that the shift from public to private is most important. Reference to specific places may not always be understood, but Westerkamp expects that each listener’s personal (that is, private) life experiences will allow him to relate to these general spaces in a meaningful way. One may not have been by the river on Salt Spring Island, but certainly most will have experienced rivers, lakes, oceans: water.

Andra McCartney refers to Westerkamp’s æsthetic goal of “knowing one’s place,” which she explains is Westerkamp “trying to understand as much as possible about the social, political, ecological and acoustic aspects of a location before creating a piece based on sounds recorded in that place” (McCartney 2006, 34). This desire is possibly a significant factor in her frequent choice to use sounds from her own home soundscapes — Vancouver, the Canadian West Coast, and northern Germany.

A sense of place is intrinsically entwined with her sense of home and identity. Identities, just like narratives, are not set and can only be inferred by the observer and constructed or performed by the individual.

Westerkamp, then, does not express an objective identity in her works, but a performance of self whose inscribed code is there to be “read” by the listener.

In addition to the experience of public spaces through private memory, soundscape elements shift to private spaces through private listening experiences — namely, the home stereo and personal listening devices. This private listening space creates an automatic intimacy: the sounds heard are just for the listener; voices heard, even of crowds, seem inside the listener’s head when heard through headphones (Dibben 2009); extraneous noises are shut out to allow a more intensified, detailed listening experience (Stern 2003). The sounds of nature fill the private space, creating an intimacy perhaps only rarely experienced in the original public space.

One specific example of this blur between public and private is the use of the raven call in MotherVoiceTalk. While on Salt Spring Island, Westerkamp recorded various raven calls. In the call of two ravens on her first morning there, Westerkamp identified a conversation, not unlike the one she wished to have with Kiyooka on that same island. She explains that “a deeply sonorous two-tone call” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 4) sounded like Kiyooka’s intonation of “my mother.” To emphasise this parallel, Westerkamp includes this raven call near the beginning of MotherVoiceTalk during which we hear Kiyooka state “my mother” repeatedly. Westerkamp uses another raven call to imitate Kiyooka’s dry laugh (“ha ha ha”) heard throughout the piece. She repeats the raven call “three times in a certain tempo and [it sounds] more typically raucous” (Ibid., 5). Like the shape-shifting raven of Native American mythology (Lynch and Roberts 2010, 93), these raven calls become the voice of Kiyooka; for Westerkamp, who is searching for a way to meet with him on Salt Spring Island, the raven comes as Kiyooka’s reincarnation, a means to a private encounter.

The voices heard in MotherVoiceTalk share personal stories, some of joy and others of sorrow. These private memories become public in this work. The boundary between private and public, which is blurred by the use of such stories, is essential to the expressivity of MotherVoiceTalk: the listener is moved by the personal stories and inspired to reflect on his own. Just as private becomes public in the electroacoustic world, so too do public soundscapes gain subjective, personal meaning through Westerkamp’s manipulations. The intimacy of hearing the water and ravens allows the listener to immerse himself in the environment. The raven in particular moves beyond a general public soundscape element to become the “voice” of Kiyooka, a voice that can converse with Westerkamp and the listener.

Constructing Identity: Mothers, the Motherland and a Mothertongue

In What Can She Know? (1991), feminist epistemologist Lorraine Code evaluates the objective, autonomous view of epistemology, favouring instead a more relative epistemology that considers the identity of the knower (which includes the knower’s sex) as essential and recognises the often processual nature of knowledge acquisition, including the process of constructing identity in relation to the world. In her discussion of Westerkamp, McCartney applies Code’s notion of “second persons”, or “someone with whom we interact in order to learn the important characteristics of personhood” (McCartney and Waterman 2006, 6), which, as Code herself asserts, poses a strong alternative to autonomous notions of knowledge (Cartesian) or to certain feminist conceptions of subjectivity, such as Sara Ruddick’s “maternal thinking”. 7[7. Code criticizes Ruddick’s “maternal thinking” because it “[posits] an ideal of ‘wholeness’ with prescriptive dimensions that have the potential to oppress women by inducing as much guilt as older, autonomy-prescriptive positions have done” (Code 1991, 93).]

The relational perspective of knowledge acquisition in “second-person relations” counters the male-associated focus on individuality. McCartney suggests that this is an important way to foster women electroacoustic composers; through partnerships and mentoring, women learn how to be electroacoustic composers. But beyond this application, Code’s “second persons” appears as an important theme in Westerkamp’s œuvre.

The people after whom we first model personhood are our parents, and, traditionally, our mothers in particular. MotherVoiceTalk is a sonic meditation of this second-person relation, the importance of which we can observe in Roy Kiyooka’s words and Westerkamp’s compositional choices. MotherVoiceTalk enacts a self-reflective process through which Westerkamp examines her identity in relation to an “other”, namely between herself as daughter and her mother.

Mothertalk reflects on the often complicated second-person relationship that can exist between mother and child and the ongoing identity construction children go through in relation to their mothers. The book suggests that it was not uncommon in the early twentieth century to send children to live with other either wealthier or childless relatives in order to relieve the financial strain of an ever-growing family. Mary Kiyooka’s two eldest children (Roy’s older siblings) spent many years in Japan with her and her husband’s families: George didn’t return to Canada until he was a teenager, Mariko until she was in her 40s. Particularly for Mariko, much bitterness persisted because she felt abandoned; she did not have the opportunity to learn personhood from the figure from whom she most desired it. Mary confesses an emotional estrangement from George and a difficult re-acquaintance with Mariko, with whom she lived until she died. In Mothertalk, Mary explains that, despite deep love felt and expressed through letters, the physical separation from George and Mariko when they were young (and in Mariko’s case, until adulthood) contributed to a lifelong emotional alienation that proved hard to overcome. Roy himself continued to visit his mother in order to feel connected to her and his Japanese heritage. 8[8. Mary explains in the book that Roy visits her the most out of all her children besides Mariko, who lived with her during the period of the interviews.] Despite access to telephone technology, it was the in-person interactions that best connected him with her and his Japanese identity:

I’ve been talking of how my mother gave me my first language, a language I began to acquire even as I suckled on her breast, and what a motley mode of speaking it’s all become in time. Need I say, that she couldn’t save me from that fate. But I have seen a look on her face that told me she understood (wordlessly…) the ardour of all such displacement. Thus it is that I always speak Japanese when I go home to visit her. More than that I can, for the time being, become almost Japanese. I realize that it’s one of the deepest “ties” I have in my whole life. (Kiyooka 1997, 183)

Kiyooka began interviewing his mother in the 1980s, while she was in her 90s, in order to preserve her stories before her physical body failed. Similarly, Westerkamp felt an urgency to preserve her 100-year-old mother’s stories. While Westerkamp was composing MotherVoiceTalk, a process that saw her examining the relationship between Kiyooka and his mother, particularly in her later years, Westerkamp visited her own mother, Agnes Westerkamp, in Germany. Westerkamp found an affinity to Kiyooka’s relationship to his mother, and between the two mothers themselves:

Hearing her [Mary Kiyooka], and the way Roy spoke about her, I sensed that she must have been as powerful a woman as my own mother. Both had gone through the hardships of war and political changes, but had not been crushed by them. … Both Roy and I chose to stay in close touch with our mothers: we got to know them better in their old age and conducted interviews with them. It seems that both our mothers loved to reminisce and tell stories. (Westerkamp forthcoming, 9–10)

Because of these connections and the timing of being with her mother as she was working on MotherVoiceTalk, Westerkamp included her mother’s voice in the composition as well. These conversations with their mothers helped them connect “with their powerful female presence in us…” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 6). She includes the voices of both mothers, often layering them over each other, panning them back and forth. The specific meaning of their words is lost, and, thus, rendered insignificant — many native English speakers might not understand these languages anyway. By layering and panning their voices, their words and sounds become symbols for motherhood. Westerkamp further emphasizes the equivalence of their symbolic significance, rather than the differences of their linguistic meaning, by panning the two mothers’ voices back and forth; they continually move and cross each other (Audio 2). The panning of their voices, particularly when they cross over each other, creates a kind of sonic equivalence as the distinct sounds of their voices and the linguistic content are sometimes lost. Rather than keeping them as discrete characters in separate positions in the mix (for example, one in the far left and one in the far right), Westerkamp treats their voices metaphorically. Their voices stand in for “mother” — a central figure in a child’s journey to self-identify. Their voices also signify the “otherness” that was part of Roy Kiyooka and Westerkamp’s immigrant experiences.

According to Nicola King (2000), memory is our only access to events; these events are articulated through language. King’s book focuses primarily on the relationship between memory, the body and language in processing and articulating abuse. While the intensely traumatic stories in King’s book may seem far removed from the stories captured in MotherVoiceTalk, in fact, it is precisely the latter’s documentation of immigrant experiences that parallels some of these traumatic connections among memory, body and language. For example, not only did Mary experience years of struggle as a young bride in Canada, trying to feed and support her family, but the Kiyooka family also had to retreat to a small Albertan town to escape persecution during World War II when their bodies and language displayed their disdained “otherness”. King highlights Edward Casey’s (1987) notion of embodied memory, that is, memory that “is constitutive of our experience of living in time” (King 2000, 27). Thus, King states, “the body itself is imagined as an archaeological site which preserves the experience of the past” (Ibid., 15). And... the experiences of the past “are inevitably reconstructed in language… ” (Ibid.). In MotherVoiceTalk, we hear Mary reconstruct through her first language — Japanese — the past, a past based on hardships and vilification. As I will discuss below, Kiyooka reflects on his dual identity through a corporeal metaphor: umeiboshi throat; his “otherness”, which can also be seen in his physical appearances, manifests in the language of the stories that emerge from his umeiboshi throat.

Language is central to both identity and relationships (i.e., bonding) in Mothertalk. This is a testament to Kiyooka’s own preoccupation with language, a preoccupation Westerkamp continues in MotherVoiceTalk. As a Japanese-Canadian immigrant, Kiyooka found that language acted at once as a means of both attachment and alienation. Mary felt a connection to home (Tosa, Japan) — both a specific place and a feeling — through the letters written in Japanese that her father sent to her in Canada. Because Mary never became fluent in English and most of her children didn’t become fluent in Japanese 9[9. George and Mariko spent many years in Japan, so they were fluent in Japanese; however, the alienation persisted because of the physical rather than linguistic divide.], language became a barrier to the mother-child connection. Mary in fact explains that she didn’t teach her children her native language because “the desire to rid ourselves of our immigrant status was very strong” (Kiyooka 1997, 151). Even Kiyooka, though he had sufficient Japanese fluency, arranged for a translator to interview his own mother. It was only through this external mediator that Mary could share with her son and he could hear her story.

For Kiyooka, though, it was this Japanese language, at once foreign and familiar, that connected him to the other half of his dual identity, Japanese-Canadian: “She and she alone reminds me of my Japanese self by talking to me in the very language she taught me before I ever had the thot [sic] of learning anything” (Kiyooka 1997, 182). As an English language learner, Westerkamp related to Kiyooka’s experience of reconciling two ethnic identities:

… for those of us who carry a first language and culture inside us, different from the second language and culture in which we now live and function, our ears are alert in a specific way, always trying to decipher the meanings of the culture and environment we joined later in our lives, trying to negotiate our way through it. (Westerkamp forthcoming, 5)

Westerkamp’s commission for the Kiyooka project was to derive inspiration from his output, which includes numerous paintings, sculptures, photographs and books of poetry. Much of Kiyooka’s poetry also ponders his experience as a Nisei (second-generation, Canadian-born, child of Japanese immigrants) and its impact on his family, both siblings and parents. Some of these poems are interspersed in Mothertalk, a decision made by the editor, Daphne Marlatt, in consultation with Kiyooka’s daughter, Fumiko. Of all of Kiyooka’s life and work, Westerkamp was most drawn to his Japanese-Canadian past (in particular his young adulthood during World War II) in the context of his role as a prolific and respected artist in the English-Canadian cultural scene. She remarked: “Like me, Kiyooka grew up in another cultural context. … Kiyooka and I — in common with all immigrants — carried within us another culture and learned more or less to integrate it into the cultural environment of the new world” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 4–5). The decision to focus on Mothertalk and its source material (i.e., interview tapes) speaks to Westerkamp’s own preoccupation about polyphonous identities: at once Canadian and German, both insider and outsider, with these elements always foregrounded in the relationship with her German mother.

Westerkamp’s use of the mothers’ voices, both in foreign languages, displays their symbolic signification as “other”. Westerkamp had access to many of Roy Kiyooka’s recordings and documentations as well as the recordings of Masutani interviewing Mary Kiyooka. Though she did not understand the Japanese language spoken on the tapes, she was inspired by this “rich sonic world” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 9):

I found her voice extremely interesting in its power and expressiveness, its varied intonations. When it came to selecting excerpts for possible use in the composition, I was guided by listening for interesting intonations, strong expressions of emotions such as crying or laughing, hearing place names and names of her children, or other words I might recognize, such as “samurai.” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 9) 10[10. Mary Kiyooka’s father was a samurai, and this was a source of pride for her family and a central aspect of her Japanese identity.]

One key sonic element that highlights the immigrant experience (which highlights a self vs. other struggle) in MotherVoiceTalk is the phrase “umeiboshi throat”. This phrase appears often in Kiyooka’s works, and Westerkamp includes an excerpt of one such poem in MotherVoiceTalk: “Why I am prone to ask myself why does this midnight litany with all your voices enthral the yet-to-be-born throngings in my umeiboshi throat?” 11[11. Unknown source. When I asked Westerkamp about the source of this quotation, she explained that it was from one of his poems, but she didn’t know which one; she was using a recording in which this passage was stated.] Though the word umeiboshi refers to a traditional Japanese food, Westerkamp suggests that Kiyooka’s use of the word means a Japanese voice: “Kiyooka’s own voice, born and steeped in a strong Japanese tradition” (Westerkamp forthcoming, 6). His use of the phrase fits with Westerkamp’s interpretation. The phrase combines a Japanese and an English word, much in the same way that he must combine the two cultural and linguistic worlds. His poetry often includes Japanese words; Kiyooka explains: “Given who I am that is inevitable” (Ibid.). Westerkamp allows Kiyooka to meditate on his “umeiboshi throat” in MotherVoiceTalk by including several repetitions of the phrase, each of which moves further away into the auditory horizon, and becomes increasingly processed, the effect of which is the impression that the phrase and its significance are being internalized.

Just as Kiyooka’s words have prompted Westerkamp’s reflections throughout the piece 12[12. Recall that Kiyooka opens the work with “my mother” and his intention to record his mother; Westerkamp then states “my mother” and also speaks of her creative intention. Kiyooka talks first about his mother; then Westerkamp talks about hers. Mary’s voice is heard before Agnes’.], Westerkamp now states “with [her] German accent” the same phrase: umeiboshi throat.

Given the stories of Roy, Mary, and Agnes in particular (who all lived during World War II), “umeiboshi throat” signifies not only the curious experience of bilingualism and immigrants, but also the betrayal they experienced during World War II when their umeiboshi throats declared them as enemies to the Allies. Kiyooka’s family was forced to move to a small town in Alberta in order to escape persecution (though internment was unlikely) during World War II. He quit high school in order to work, and he never received his high school diploma. In her biographical discussion of Westerkamp, Andra McCartney discusses the impact of Westerkamp’s German experience in her childhood and youth: “As part of the generation of Germans who were born just after the Second World War, Westerkamp lived with the grief and shame that younger Germans have inherited from events that happened before their birth[s], during the Nazi time” (McCartney 1999, 148).

MotherVoiceTalk enacts an identity construction as both Kiyooka and Westerkamp reconcile themselves in relation to their mothers and to their immigrant status. While Code’s second-person relationship suggests a deep affinity between the person and his second person, who acts as a model, the increasing separation and independence from this second-person relationship is similarly crucial to identity construction. In MotherVoiceTalk, both Kiyooka and Westerkamp define themselves in relation to and separate from their mothers. This identity construction is most evident in Kiyooka’s and Westerkamp’s reflection on their immigrant status. As immigrants, they both gain “insider” access to Canadian culture, but their connection to another culture, language and country, particularly through their mothers, continues to keep them on the outside as “the other”.

Storytelling in MotherVoiceTalk: Defying Time and Space

In MotherVoiceTalk, Westerkamp weaves multiple narratives within her own musical narrative; her processing and mixing negotiate the boundaries of time and space as we understand them in reality. Her musical narrative is based on a linguistic narrative constructed by the voices of Hildegard, her mother Agnes, Roy and his mother, Mary. With the voices of Roy and his mother comes the narrative of Mothertalk, which itself is an amalgam of narratives — individual and collective — that tell the stories of Mary and her family.

In comparison to non-fixed medium music (e.g., instrumental music), electroacoustic music has the technological, and thus æsthetic and expressive, privilege to sample recordings of people’s conversations, speeches, and such. Thus, without requiring the individual to be present, in real time, her life — the stories — can be offered as a narrative through language, which “displays its power to voice experiences, to bring about shared understandings of life events, [and] to shape and transform individual and collective realities” (De Fina 2003, 1). An electroacoustic work can communicate not only the narrative (linguistic and/or musical) of the composer, but also that of the sampled voice. In MotherVoiceTalk, Westerkamp incorporates recordings of Roy Kiyooka talking about the MotherTalk project, interviews between Mary and Masutani (the translator), Westerkamp’s interviews with her mother, and Westerkamp discussing the project in field recordings (at Salt Spring Island).

MotherVoiceTalk transcends the immovable boundaries of space and time to bring together Roy, Mary, Hildegard and Agnes. But the layering of stories, times, and places is complex; for example, in Mary’s stories alone, there are layers of time: events (past), memory of the past (past, but closer to present), and the telling of (the memory of) an event (King 2000). Westerkamp sonically preserves impressions of past and present primarily through placement on the auditory horizon, a placement that is achieved through a manipulation of dynamics, varied use of reverberation and equalization (e.g., filtering out low and high-frequency bands). The equalization of the mothers’ voices probably already occurred naturally to some degree by nature of the recording; it is unlikely that Roy and Hildegard placed a microphone close to their mothers’ mouths. The distance created in the initial acoustic “mix” would be transduced in the original interview recordings. But Westerkamp intentionally constructs a temporal distinction with Roy’s voice in particular, through the use of reverberation and filtering to produce a fuzzier sound. He sounds distant from the listener, just as he was distant in time and space from Westerkamp during this process. Westerkamp varies her manipulation of his voice, but it is never “dry” and close; his voice, and thus his presence, is always relegated to the past. By contrast, Westerkamp’s voice is almost always “dry”. As in a documentary, her voice seems to be narrating a process of reflection that is ongoing, in the present; and though the listener knows this reflection took place in the past, the vocal staging of Westerkamp’s voice invites the listener to reflect in his own present.

Westerkamp attempts to sonically transcend the barriers of time and space to engage with Kiyooka’s story by paralleling it in two key ways. First, she includes an introductory “creative agenda” from both herself and Kiyooka. Near the opening of MotherVoiceTalk, Westerkamp includes a recording of Kiyooka explaining his plan to interview his mother, followed by Westerkamp’s own statement of intent 13[13. Westerkamp also included a similar introduction in Moments of Laughter (1988), in which the speaker explains the context, purpose and/or methodology of the unfolding work. The presence of a statement of intent as part of the finished piece recalls Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room.]:

In the summer of 1986, my mother came out to spend the summer with me in Vancouver; so she was 90 years of age at the time. And we decided that summer that we would record her conversation about her life. It was spoken in Japanese. When my mother and I speak to each other, we have always spoken in Japanese, rarely in English.

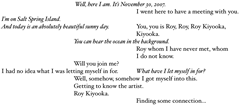

Westerkamp’s statement of intent also captures the complexity of time and space in this work by constructing both past and present experiences in her multiple voices. Through a layering of her multiple voices, Westerkamp attempts to create some temporal distinction in her opening statement (Fig. 1). As Westerkamp describes her project (to “meet” with Roy Kiyooka), she uses varied placement on the horizontal and vertical planes, and on the auditory horizon, to differentiate between the event of the far past (November 30, 2007), the reflection on or memory of the event in the more recent past (“I went here to have a meeting with you” [emphasis mine]) and the listener’s present (“Will you join me?” 14[14. This question could be posed to Roy Kiyooka as a follow up to “I went here to have a meeting with you.” However based on placement, with a significant break from the opening second-person reference to Kiyooka (“I went here…”), this question is more readily heard as an invitation to the listener.]).

Second, Westerkamp further attempts to negotiate the real-life boundaries between time and space by constructing an imagined conversation through the recordings. Kiyooka and Westerkamp never met in person, but at times in MotherVoiceTalk, Westerkamp edits their voices so that it imitates the back-and-forth of a real conversation.

That Westerkamp never met Roy or Mary Kiyooka, and that both Roy and Mary were dead when Westerkamp composed MotherVoiceTalk is no barrier in the age of sound reproduction. The recorded voices break the boundaries of reality and can emerge in new and impossible circumstances. In MotherVoiceTalk, Westerkamp creates a conversation with Roy Kiyooka and constructs a complex spatial representation of time in the far past, past and present.

Conclusion

When Westerkamp began to immerse herself in Kiyooka’s artistic output, she was overwhelmed by its enormity. But she found herself drawn to the similarities she perceived between their lives, a link she found with a man she had never met. As a Canadian immigrant herself, who had to negotiate two cultures, two languages and two homes, she identified with this similar struggle in Roy Kiyooka’s life. They both had mothers whose stories helped Kiyooka and Westerkamp define their own life stories and construct identities. In MotherVoiceTalk, several meetings occur: two artists; mother and son; mother and daughter; Germany, Japan and the Canadian West Coast. Westerkamp uses the technological capabilities of the studio to create a musical space where negotiations are made between private and public, the self and the other, and time and space, resulting in a work whose blurred boundaries allow the listener an opportunity to reflect on his or her own stories before they are only “like a memory….”

Bibliography

Altman, Rick. “Sound Space.” In Sound Theory, Sound Practice. Edited by Rick Altman. New York; London: Routledge, 1992, pp. 46–64.

Casey, Edward. Remembering: A Phenomenological Study. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Code, Lorraine. What Can She Know? Feminist Theory and the Construction of Knowledge. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Collins, Nick and Julio d’Escriván. The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music. Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

De Fina, Anna. Identity in Narrative: A Study of Immigrant Discourse. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2003.

Dibben, Nicola. “Vocal Performance and the Projection of Emotional Authenticity.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Popular Musicology. Edited by Derek B. Scott. Surrey, England: Ashgate, 2009, pp. 317–34.

Hodgson, Jay. “Navigating the Network of Recording Practice — Towards an Ecology of the Record Medium.” Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. Department of Music, University of Alberta, Canada, 2006. ProQuest (AAT NR13988).

King, Nicola. Memory, Narrative, Identity: Remembering the Self. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Kiyooka, Roy. Mothertalk: Life Stories of Mary Kiyoshi Kiyooka. Edited by Daphne Marlatt. Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1997.

Lynch, Patricia Ann and Jeremy Roberts. Native American Mythology A to Z. 2nd edition. New York: Chelsea House, 2010.

McCartney, Andra. “Sounding Places: Situated Conversations Through the Soundscape Compositions of Hildegard Westerkamp.” Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. York University (Canada), 1999. ProQuest (AAT NQ46305).

_____. “Gender, Genre and Electroacoustic Soundmaking Practices.” Intersections: Canadian journal of music / Revue canadienne de musique 26/2 (June 2006), pp. 20–48.

McCartney, Andra and Ellen Waterman. “Introduction: In and Out of the Sound Studio.” Intersections: Canadian journal of music / Revue canadienne de musique 26/2 (June 2006), pp. 3–19.

Stern, Jonathan. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Westerkamp, Hildegard. “An Imaginary Meeting — The Making of MotherVoiceTalk.” (2008). In The Art of Immersive Soundscapes. Edited by Pauline Minevich, Ellen Waterman and James Harley. Regina: University of Regina Press, forthcoming.

Social top